|

Excerpt - An Introduction to Henry VIII

|

Henry VIII - Welcome to the Website

By Mark Holinshed

A Summary, here follows a succinct account of the years 1509 to 1547, bringing life to the role of his six wives and the men and women who created the episodes leading to the Reformation. Follow the tumultuous events of Cardinal Wolsey’s tribulations with the papacy over the divorce of Catherine of Aragon. The Boleyn era, the rise of Thomas Cromwell and the Seymours, the break with Rome, a third marriage, this time to Jane. The Dissolution of the Monasteries, Cromwell’s disastrous alliance with the Germans and Anne of Cleves, enter and exit jezebel Howard, Catherine, promoted by her uncle Thomas Duke of Norfolk, another execution, on to the end, Catherine Parr and the aged kings last years.

A Boy King

Henry VIII was seventeen years old when he became King of England after the death of his father, Henry VII, in April 1509. Until the death of his older brother, Arthur, in 1502, he had not expected to be the royal ruler of England.

With the pope’s authority, the adolescent new king was married to his brother’s widow, Catherine of Aragon, who was six years older than Henry, on 11 June 1509.

‘The king is young’, lamented the Spanish ambassador in England, ‘and does not care to occupy himself with anything but the pleasures of his age. All other affairs he neglects.’ At first the young king’s father’s aged contemporaries conducted government, but soon they became dominated by a younger and ruthlessly ambitious clerical man, Thomas Wolsey.

Wolsey began the reign as Henry VIII’s almoner but, as the youthful king pursued his gaming pastimes, Wolsey expanded his control and rose meteorically, unchecked, from almoner to papal legate in a few years.

With the pope’s authority, the adolescent new king was married to his brother’s widow, Catherine of Aragon, who was six years older than Henry, on 11 June 1509.

‘The king is young’, lamented the Spanish ambassador in England, ‘and does not care to occupy himself with anything but the pleasures of his age. All other affairs he neglects.’ At first the young king’s father’s aged contemporaries conducted government, but soon they became dominated by a younger and ruthlessly ambitious clerical man, Thomas Wolsey.

Wolsey began the reign as Henry VIII’s almoner but, as the youthful king pursued his gaming pastimes, Wolsey expanded his control and rose meteorically, unchecked, from almoner to papal legate in a few years.

Wolsey Rules England for a Malleable Monarch

Above Images - Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon, Queen of England

Wolsey craved control, and the highest office a cleric could achieve was that of pope. Through the papacy, Wolsey believed, he could rule all of Christendom and restore its authority and prestige to levels not seen since the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

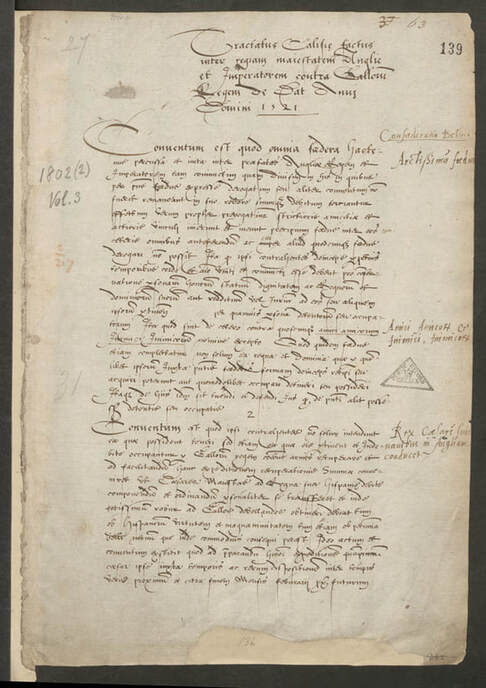

The houses of Trastámar (from which Catherine of Aragon descended), Habsburg and Valois were the principal ruling dynasties in Europe, and bloody and expensive wars were waged between them. In 1518, Pope Leo X launched an enterprise to bring a lasting peace to Christendom, but Wolsey, using his authority as papal legate, usurped the pontiff’s initiative and supplanted it with a pact of his own design, the Treaty of London.

The following year, however, Maximilian, head of the Habsburg dynasty and Holy Roman Emperor, died. His grandson, nineteen-year-old Charles V, who was already (by his maternal Trastámar inheritance) King of Spain, inherited Maximilian’s Habsburg domains and thus Trastámar and Habsburg united to become a vast empire.

The title of Holy Roman Emperor, the holder of which was guardian of the Roman Catholic Church, was decided by election, and it fell vacant upon Maximilian’s death.

The houses of Trastámar (from which Catherine of Aragon descended), Habsburg and Valois were the principal ruling dynasties in Europe, and bloody and expensive wars were waged between them. In 1518, Pope Leo X launched an enterprise to bring a lasting peace to Christendom, but Wolsey, using his authority as papal legate, usurped the pontiff’s initiative and supplanted it with a pact of his own design, the Treaty of London.

The following year, however, Maximilian, head of the Habsburg dynasty and Holy Roman Emperor, died. His grandson, nineteen-year-old Charles V, who was already (by his maternal Trastámar inheritance) King of Spain, inherited Maximilian’s Habsburg domains and thus Trastámar and Habsburg united to become a vast empire.

The title of Holy Roman Emperor, the holder of which was guardian of the Roman Catholic Church, was decided by election, and it fell vacant upon Maximilian’s death.

Above Image - Cardinal Thomas Wolsey

A Bloody Rivalry

By this time, twenty-five-year-old Francis I had been King of France for four years. The union of Trastámar and Habsburg territories now surrounded France – save control of the Strait of Dover. In an effort to rebut Charles’s escalation of power, Francis set himself against Charles for election as Holy Roman Emperor.

Francis lost the election, and thereafter followed an escalation of the intense and bloody rivalry between Habsburg and Valois.

Cardinal Wolsey exploited the tradition that Holy Roman Emperors elect were first crowned King of the Germans at Aachen Cathedral in Germany. Charles lived in Spain, and safe passage between his domains was essential. Wolsey invited Charles to visit England as he sailed from Spain for the coronation. Charles then, appointed his former tutor, the trusty Adrian of Utrecht, as his regent in Spain and set off for Germany via England. Guarded in the Channel by the English fleet, he was protected from French hostility.

Charles arrived just as an enormous maritime logistics spectacle, arranged by Wolsey, was underway in the ‘narrow sea’ between Dover and Calais. The display was part of the preparations for the famous meeting between Henry VIII and Francis I known as the Field of the Cloth of Gold.

Wolsey had shown himself to be the de facto ruler of England, and he set out to imbue these two young monarchs with a lasting impression. He left them in no doubt about the strength of the English navy in the narrow sea.

Having been made welcome during his stay, the emperor then continued to Germany and his coronation.

The newly crowned Holy Roman Emperor was still in his northern territories when Wolsey’s London peace treaty was breached, and the cardinal reappointed himself the peacemaker.

At a clandestine meeting with Charles in Bruges, he reinforced his position as a critical ally if the emperor were to be an effective ruler of geographically distant lands. Wolsey would pledge his support to Charles and arrange his safe passage back to Spain through the Strait of Dover. Wolsey also agreed to make war on Francis in the north of France to draw his forces away from Charles' ambitions in the south.

In return, Charles would secure Wolsey's election as pope, by force if needs be.

Shortly afterwards Pope Leo X died, but it was not Wolsey who became pope but the trusty Adrian. He became Pope Adrian VI.

Francis lost the election, and thereafter followed an escalation of the intense and bloody rivalry between Habsburg and Valois.

Cardinal Wolsey exploited the tradition that Holy Roman Emperors elect were first crowned King of the Germans at Aachen Cathedral in Germany. Charles lived in Spain, and safe passage between his domains was essential. Wolsey invited Charles to visit England as he sailed from Spain for the coronation. Charles then, appointed his former tutor, the trusty Adrian of Utrecht, as his regent in Spain and set off for Germany via England. Guarded in the Channel by the English fleet, he was protected from French hostility.

Charles arrived just as an enormous maritime logistics spectacle, arranged by Wolsey, was underway in the ‘narrow sea’ between Dover and Calais. The display was part of the preparations for the famous meeting between Henry VIII and Francis I known as the Field of the Cloth of Gold.

Wolsey had shown himself to be the de facto ruler of England, and he set out to imbue these two young monarchs with a lasting impression. He left them in no doubt about the strength of the English navy in the narrow sea.

Having been made welcome during his stay, the emperor then continued to Germany and his coronation.

The newly crowned Holy Roman Emperor was still in his northern territories when Wolsey’s London peace treaty was breached, and the cardinal reappointed himself the peacemaker.

At a clandestine meeting with Charles in Bruges, he reinforced his position as a critical ally if the emperor were to be an effective ruler of geographically distant lands. Wolsey would pledge his support to Charles and arrange his safe passage back to Spain through the Strait of Dover. Wolsey also agreed to make war on Francis in the north of France to draw his forces away from Charles' ambitions in the south.

In return, Charles would secure Wolsey's election as pope, by force if needs be.

Shortly afterwards Pope Leo X died, but it was not Wolsey who became pope but the trusty Adrian. He became Pope Adrian VI.

Above Image -Embarkation at Dover for the Field of Cloth of Gold and the 1521 Treaty of Bruges

Wolsey's Bid for the Papacy

The time came for Charles to return home to Spain, and as agreed at Bruges, the English navy would again protect the emperor from French hostility in the Channel. Charles had pacified Wolsey, Adrian was an aged stand-in and would not last long in the papal office. He promised he would secure Wolsey’s election as pope at the next opportunity.

The Bruges agreement called for England and the Habsburg Empire to join forces and declare war on France, and this began with attacks on French naval ports as Charles sailed through the Channel.

Wolsey had honoured his side of the bargain and Charles sailed safely back to Spain.

A joint land invasion of France began in 1523, however, during that incursion, as the Duke of Suffolk was about to attack Paris, news came that the aged Adrian was dead.

The new pope was Giulio di Giuliano de' Medici, Pope Clement VIII and not the English cardinal.

Wolsey was incandescent. He was full of rage, a man set on bloody revenge against the emperor. For him, this was a betrayal in the first degree.

Without a word to Henry VIII, Wolsey changed sides from the Habsburg Charles to the Valois Francis. He embarked on an alliance to build a Valois-backed initiative to make him pope, with French support; however, in so doing, he severed the supply line to Brandon and left him stranded south of the River Somme, just when Paris had been ripe for the taking.

To maintain his papal ambitions, the cardinal must rid Henry VIII of his queen, Catherine of Aragon. Ostensibly, Henry and Catherine were happy in their marriage, but Charles V was Catherine’s nephew and so now, to the chameleon cardinal, she was a liability – she had no place in his alliance with the French. Henry must divorce her for a French wife.

The Bruges agreement called for England and the Habsburg Empire to join forces and declare war on France, and this began with attacks on French naval ports as Charles sailed through the Channel.

Wolsey had honoured his side of the bargain and Charles sailed safely back to Spain.

A joint land invasion of France began in 1523, however, during that incursion, as the Duke of Suffolk was about to attack Paris, news came that the aged Adrian was dead.

The new pope was Giulio di Giuliano de' Medici, Pope Clement VIII and not the English cardinal.

Wolsey was incandescent. He was full of rage, a man set on bloody revenge against the emperor. For him, this was a betrayal in the first degree.

Without a word to Henry VIII, Wolsey changed sides from the Habsburg Charles to the Valois Francis. He embarked on an alliance to build a Valois-backed initiative to make him pope, with French support; however, in so doing, he severed the supply line to Brandon and left him stranded south of the River Somme, just when Paris had been ripe for the taking.

To maintain his papal ambitions, the cardinal must rid Henry VIII of his queen, Catherine of Aragon. Ostensibly, Henry and Catherine were happy in their marriage, but Charles V was Catherine’s nephew and so now, to the chameleon cardinal, she was a liability – she had no place in his alliance with the French. Henry must divorce her for a French wife.

Read More - Wolsey's Aspirations for Papacy

Above Image - Pope Adrian VI

The Cardinal Turns French

Wolsey’s change of allegiance to the Valois King of France and his family began with near disaster when Francis was captured during the battle of Pavia and then held prisoner by Charles in Spain. Wolsey, however, was quick to take advantage and formed a bond with Francis’s mother, Louise, and his sister, Marguerite d’Angoulême.

Wolsey began a process of tireless work in support of the French negations for Francis’s release, and his efforts unified the two nations against Charles. Francis was eventually freed and, as soon as he was back on French soil, he formed a league against Charles.

Cardinal Wolsey and Francis had set themselves together as bitter enemies of Charles.

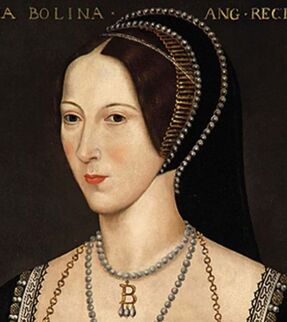

Wolsey probably had Francis’s sister, Marguerite d’Angoulême, in his mind to marry Henry, but the French princess was too shrewd for that ploy and instead, with a little genealogical conjuring, nominated her protégé Anne de Boulogne.

The cardinal convinced Henry and Anne that he could secure a divorce sanctioned by the pope. After the Sack of Rome in 1527, Pope Clement fled to the clifftop hideaway of Orvieto, in south-western Umbria.

In reality, the only way that a divorce could be obtained was with Wolsey as pope with French backing. Catherine of Aragon was Charles' aunt. Charles was the Holy Roman Emperor, and the Holy Roman Emperor controlled the pope who his prisoner on a remote hill top.

During the pope’s exile therefore, Wolsey advocated that papal authority should be transferred to him, which would have given him the mandate to rule as he wished concerning Henry’s marriage. Wolsey went to France and incited the opposing sides on mainland Europe, but, while he was away, the de Boulogne faction tightened its controlling grip on Henry. Anne, her father and her brother – aided by Louise and Marguerite d’Angoulême and Francis – gradually they stole the naive king from Wolsey, manoeuvring him into their clutches.

Wolsey dashed home – he must at least delay if not scupper the divorce and remarriage entirely – but it was too late; he had over-reached himself.

The Blackfriars trial of Henry VIII’s marriage to Catherine famously collapsed without a decision in July 1529. Wolsey had failed his king. The legal arguments were an irrelevance anyway, they always had been. Wolsey’s only chance, and remote one at that, of succeeding with papal sanction for the divorce was to obtain the papacy for himself. Catherine was Charles’s aunt. Charles was the most powerful man in Christendom, and he was guardian of the pope. Even if hell were to freeze over he still would not have allowed such a humiliation to be inflicted on his family.

Wolsey began a process of tireless work in support of the French negations for Francis’s release, and his efforts unified the two nations against Charles. Francis was eventually freed and, as soon as he was back on French soil, he formed a league against Charles.

Cardinal Wolsey and Francis had set themselves together as bitter enemies of Charles.

Wolsey probably had Francis’s sister, Marguerite d’Angoulême, in his mind to marry Henry, but the French princess was too shrewd for that ploy and instead, with a little genealogical conjuring, nominated her protégé Anne de Boulogne.

The cardinal convinced Henry and Anne that he could secure a divorce sanctioned by the pope. After the Sack of Rome in 1527, Pope Clement fled to the clifftop hideaway of Orvieto, in south-western Umbria.

In reality, the only way that a divorce could be obtained was with Wolsey as pope with French backing. Catherine of Aragon was Charles' aunt. Charles was the Holy Roman Emperor, and the Holy Roman Emperor controlled the pope who his prisoner on a remote hill top.

During the pope’s exile therefore, Wolsey advocated that papal authority should be transferred to him, which would have given him the mandate to rule as he wished concerning Henry’s marriage. Wolsey went to France and incited the opposing sides on mainland Europe, but, while he was away, the de Boulogne faction tightened its controlling grip on Henry. Anne, her father and her brother – aided by Louise and Marguerite d’Angoulême and Francis – gradually they stole the naive king from Wolsey, manoeuvring him into their clutches.

Wolsey dashed home – he must at least delay if not scupper the divorce and remarriage entirely – but it was too late; he had over-reached himself.

The Blackfriars trial of Henry VIII’s marriage to Catherine famously collapsed without a decision in July 1529. Wolsey had failed his king. The legal arguments were an irrelevance anyway, they always had been. Wolsey’s only chance, and remote one at that, of succeeding with papal sanction for the divorce was to obtain the papacy for himself. Catherine was Charles’s aunt. Charles was the most powerful man in Christendom, and he was guardian of the pope. Even if hell were to freeze over he still would not have allowed such a humiliation to be inflicted on his family.

The End of the First Era of the Reign of Henry VIII

Above Image - Anne Boleyn, Queen of England

Worse, for Wolsey, his machinations on the Continent were foiled by Archduchess Margaret (aunt of Charles V) and Louise de Valois (mother of Francis I), who saw through his treacherous schemes and united. To the exclusion of the cardinal, they negotiated a peace agreement between nephew and son, the so-called Ladies’ Peace, or Paix des Dames.

Wolsey had fallen between two stools and he was done for.

However, the ramifications of the over-reaching megalomaniac cleric’s actions amounted to significantly more even than creating discord between monarchs. The cardinal’s exploitation of the power he had filched from the church had incensed swathes of the English population.

Wolsey had fallen between two stools and he was done for.

However, the ramifications of the over-reaching megalomaniac cleric’s actions amounted to significantly more even than creating discord between monarchs. The cardinal’s exploitation of the power he had filched from the church had incensed swathes of the English population.

Wolsey’s Fall Creates a Wave of Anticlericalism

Above Images - Map of Cambrai and the Ladies, Francis' Mother Louise of Savoy , Francis' Sister, Marguerite d’Angoulême and Charles' Aunt, Margaret of Austria

Henry VIII

Henry VIII

Thus, the papal prestige that he was trying to reignite they now sought to suffocate with an anti-clerical dogma.

Anti-clericalism in this context concerned a rejection of clerical interference in secular matters and specifically of interference from a foreign power. Over previous centuries, the English Parliament had introduced legislation (such as the Statutes of Mortmain, Praemunire and Provisors) to combat such interventions, but the laws had become dormant over the past century or so. Now some of their contents was about to be reinforced, with spectacular consequences.

Anti-clericalism had reached its zenith in England at the turn of the fifteenth century, and to repress its expansion Henry V had led a diversionary war against France. It had remained a latent force throughout the consequent Wars of the Roses – but Wolsey had woken it up.

The period of hibernation was over. With Wolsey’s fall, the anti-clericalists, and there were very many of them, seized the moment. On 9 August 1529, within days of the collapse of the Blackfriars trial, the first of the Reformation Parliaments – the so-called anti-clerical Commons – was summoned.

Anti-clericalism in this context concerned a rejection of clerical interference in secular matters and specifically of interference from a foreign power. Over previous centuries, the English Parliament had introduced legislation (such as the Statutes of Mortmain, Praemunire and Provisors) to combat such interventions, but the laws had become dormant over the past century or so. Now some of their contents was about to be reinforced, with spectacular consequences.

Anti-clericalism had reached its zenith in England at the turn of the fifteenth century, and to repress its expansion Henry V had led a diversionary war against France. It had remained a latent force throughout the consequent Wars of the Roses – but Wolsey had woken it up.

The period of hibernation was over. With Wolsey’s fall, the anti-clericalists, and there were very many of them, seized the moment. On 9 August 1529, within days of the collapse of the Blackfriars trial, the first of the Reformation Parliaments – the so-called anti-clerical Commons – was summoned.

Above Image - Henry VIII

Roman Catholic Church is Illegal in England

Thomas Cromwell

Thomas Cromwell

Work was begun under the direction of Thomas Cranmer to compile the Collectanea satis copiosa (Sufficiently Abundant Collections), a book of historical documents that were said to prove that the kings of England, historically, had no superiors on earth, even in the office of the pope.

Parliament opened an attack on the clergy, and by 1532 the entire ecclesiastical establishment was on its knees, guilty of breaching the Statute of Praemunire and begging for pardon upon payment of a fine of one hundred thousand pounds.

This, however, was no way to persuade Pope Clement VII, whose office was reliant on the protection of Catherine of Aragon’s nephew, to grant a divorce from his patron’s niece and afterwards consent to the marriage of Henry to the wholly French, anti-Habsburg Anne de Boulogne.

To the anti-clericalists, the Brittonic - English, the king’s matrimonial status was a subsidiary matter. Anne had waited years, six and probably more, for her marriage to the King of England. She was ever more isolated from France but she seized an opportunity in late 1532 to revive the support of her sponsors at the French court. Catherine de’ Medici, the pope’s niece and herself of de Boulogne heritage, was pledged to marry Francis’s son Henri the following year.

Parliament opened an attack on the clergy, and by 1532 the entire ecclesiastical establishment was on its knees, guilty of breaching the Statute of Praemunire and begging for pardon upon payment of a fine of one hundred thousand pounds.

This, however, was no way to persuade Pope Clement VII, whose office was reliant on the protection of Catherine of Aragon’s nephew, to grant a divorce from his patron’s niece and afterwards consent to the marriage of Henry to the wholly French, anti-Habsburg Anne de Boulogne.

To the anti-clericalists, the Brittonic - English, the king’s matrimonial status was a subsidiary matter. Anne had waited years, six and probably more, for her marriage to the King of England. She was ever more isolated from France but she seized an opportunity in late 1532 to revive the support of her sponsors at the French court. Catherine de’ Medici, the pope’s niece and herself of de Boulogne heritage, was pledged to marry Francis’s son Henri the following year.

Anne Boleyn Appeals to France to Help Her Marry

the King of England

the King of England

Above Image - Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cromwell

Thomas Cromwell

In late autumn, a series of pageants were arranged at the English garrison of Calais and the French-governed Boulogne.

Amid all the pomp and ceremony, Francis persuaded Henry that he would not allow the wedding of his son to the pope’s niece to proceed in Marseilles unless the pope granted ‘his brother’ Henry the divorce Anne craved.

With that promise from the King of France, the reluctant Henry was persuaded that the French has sufficient influence over the pope to declare his existing marriage to Catherine of Aragon void. At last Anne had her way; she and Henry were married, probably in Boulogne,and soon she was pregnant. Anne had snared him, had seduced him by witchcraft, Henry later claimed.

The pregnancy changed everything for Henry and he battled with his conscience. The hapless king now had two wives and an heir due to be born in September – would the new child be legitimate in the eyes of God? He had hedged against the pro-French marriage to Anne de Boulogne for years but now he was forced to do something for himself and be rid of his first wife. The hard-line anti-clericals, the antipapists, began to move. The opportunity was perfect: they would use Anne de Boulogne as their vehicle to break from Rome altogether.

Amid all the pomp and ceremony, Francis persuaded Henry that he would not allow the wedding of his son to the pope’s niece to proceed in Marseilles unless the pope granted ‘his brother’ Henry the divorce Anne craved.

With that promise from the King of France, the reluctant Henry was persuaded that the French has sufficient influence over the pope to declare his existing marriage to Catherine of Aragon void. At last Anne had her way; she and Henry were married, probably in Boulogne,and soon she was pregnant. Anne had snared him, had seduced him by witchcraft, Henry later claimed.

The pregnancy changed everything for Henry and he battled with his conscience. The hapless king now had two wives and an heir due to be born in September – would the new child be legitimate in the eyes of God? He had hedged against the pro-French marriage to Anne de Boulogne for years but now he was forced to do something for himself and be rid of his first wife. The hard-line anti-clericals, the antipapists, began to move. The opportunity was perfect: they would use Anne de Boulogne as their vehicle to break from Rome altogether.

Engxit from Papal Jurisdiction

Above Image - Thomas Cromwell

Francis I

Francis I

In early 1533, Parliament outlawed all appeals to Rome. The act severed papal authority in England and allowed the new Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, to annul Henry’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon. The anti-clerical plan, from the antipapists’ point of view, had worked perfectly. The pope threatened Henry with excommunication unless he took Catherine back, and Francis’s assurances to halt the Medici marriage were trampled underfoot at Marseilles. Henry was beside himself with rage and embarrassment at his treatment by the pope and the French.

The climate was perfect for the propagation of the cause of the Henry–Johnites, descendants of the Marcher Lords and their autonomous culture.

The baby born in September to Anne de Boulogne was Elizabeth, future queen of England. Frantic moves followed to arrange a marriage for her into the French royal family, but Henry, humiliated, now fell under the influence of the Henry–Johnites. They filled his head with the injustices suffered by Henry II, King John and others at the hands of the papacy and the French in earlier reigns.

Anne had almost served her purpose to the Henry–Johnites as the vehicle to sever papal influence, and now, to finish her off, they would use her to poison the king against the French too.

The climate was perfect for the propagation of the cause of the Henry–Johnites, descendants of the Marcher Lords and their autonomous culture.

The baby born in September to Anne de Boulogne was Elizabeth, future queen of England. Frantic moves followed to arrange a marriage for her into the French royal family, but Henry, humiliated, now fell under the influence of the Henry–Johnites. They filled his head with the injustices suffered by Henry II, King John and others at the hands of the papacy and the French in earlier reigns.

Anne had almost served her purpose to the Henry–Johnites as the vehicle to sever papal influence, and now, to finish her off, they would use her to poison the king against the French too.

The de Boulogne Faction is Crushed

Above Image - Francis I, King of France

Joseph of Arimathea

Joseph of Arimathea

Cromwell crushed the de Boulogne overtures for a French marriage to baby Elizabeth.

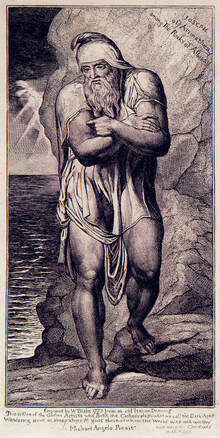

The city of Bristol, guardian of Avalon and the legend of Joseph of Arimathea, was the Henry–Johnites’ historical capital.

It was for Bristol that the royal court was bound in July 1535, just as Sir Thomas More was executed. The tour – the royal progress – was marshalled by Edward Seymour, whose family held sway in the lands that had been laid to waste during ‘the Anarchy’, the civil war between Stephen and Matilda in the twelfth-century fight for the succession of Eustace de Boulogne to the crown.

Anne de Boulogne was fearful. She had few friends in England now, and French priorities had changed in the years since Wolsey had recruited her. By the time the royal progress returned in late October, Anne was a broken woman, subjected day after day to anti-French rhetoric and Henry–Johnite taunting. Her faction was in tatters.

Early the following year, she miscarried a pregnancy, and alleged incidents on the progress were used to convict her of adultery, incest and high treason. She was executed on 19 May 1536. Within weeks, Henry’s son and potential heir, Henry Fitzroy (who had been born in 1519), was also dead, aged just seventeen.

The orchestrators of the 1535 royal progress, Edward Seymour and his family, assumed control over Henry VIII.

The city of Bristol, guardian of Avalon and the legend of Joseph of Arimathea, was the Henry–Johnites’ historical capital.

It was for Bristol that the royal court was bound in July 1535, just as Sir Thomas More was executed. The tour – the royal progress – was marshalled by Edward Seymour, whose family held sway in the lands that had been laid to waste during ‘the Anarchy’, the civil war between Stephen and Matilda in the twelfth-century fight for the succession of Eustace de Boulogne to the crown.

Anne de Boulogne was fearful. She had few friends in England now, and French priorities had changed in the years since Wolsey had recruited her. By the time the royal progress returned in late October, Anne was a broken woman, subjected day after day to anti-French rhetoric and Henry–Johnite taunting. Her faction was in tatters.

Early the following year, she miscarried a pregnancy, and alleged incidents on the progress were used to convict her of adultery, incest and high treason. She was executed on 19 May 1536. Within weeks, Henry’s son and potential heir, Henry Fitzroy (who had been born in 1519), was also dead, aged just seventeen.

The orchestrators of the 1535 royal progress, Edward Seymour and his family, assumed control over Henry VIII.

Seymour and Cromwell Rule

Above Image - Joseph of Arimathea among The Rocks of Albion

Edward Seymour

Edward Seymour

To enforce Seymour’s position, the day after Anne’s execution, his sister Jane was betrothed to the king, and they were married a few days later. Now the Seymours held the royal sanction, but there was trouble in the north: a rebellion that threatened to overturn the new regime. Known as the Pilgrimage of Grace, this revolt lasted for several months and cost many lives before it was stifled.

Jane’s tenure was short. She died after giving birth to a son named Edward, later Edward VI. The death of his sister was a setback for Seymour’s ambitions; however, he was down but not out.

After the queen’s death, Thomas Cromwell emerged as the architect of policy in England. His ambitions lay with an alliance with the German states, which, through Martin Luther and his adherents, had taken their lead from the teachings of John Wycliffe. Wycliffe’s doctrine had been prevalent in England until Henry V’s diversionary war with the French (began in 1515) and had been exported to the Continent via Anne of Bohemia (wife of Richard II), reaching a major proponent in the form of Jan Hus. The Lutherans and the Henry–Johnites were cut from the same cloth.

Jane’s tenure was short. She died after giving birth to a son named Edward, later Edward VI. The death of his sister was a setback for Seymour’s ambitions; however, he was down but not out.

After the queen’s death, Thomas Cromwell emerged as the architect of policy in England. His ambitions lay with an alliance with the German states, which, through Martin Luther and his adherents, had taken their lead from the teachings of John Wycliffe. Wycliffe’s doctrine had been prevalent in England until Henry V’s diversionary war with the French (began in 1515) and had been exported to the Continent via Anne of Bohemia (wife of Richard II), reaching a major proponent in the form of Jan Hus. The Lutherans and the Henry–Johnites were cut from the same cloth.

Cromwell’s Fatal Mismatch

Above Image - Queen of England, Jane Seymour anf her brother, Edward Seymour

Thomas Howard

Thomas Howard

Cromwell, like Wolsey before him, had over-reached himself. Francis and Charles, unlike Henry, were wise to Cromwell’s dogma and engaged Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, and consequently Howard’s young niece Catherine to blow open Cromwell’s underhand plan to achieve what his kinsman and namesake succeeded in doing a century later – to create a monarchless state.

Howard’s actions, with no little help from Bishop Stephen Gardiner, resulted in Cromwell’s downfall and execution. The Cleves marriage was annulled and Howard secured his conservative position against radical reform by arranging the marriage of his teenage niece to the ageing Henry VIII.

Howard’s actions, with no little help from Bishop Stephen Gardiner, resulted in Cromwell’s downfall and execution. The Cleves marriage was annulled and Howard secured his conservative position against radical reform by arranging the marriage of his teenage niece to the ageing Henry VIII.

Above Image - Queen of England, Anne of Cleves and Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk

Mary Queen of Scot's Threat to the Seymour

Inheritance

Inheritance

Edward Seymour

Edward Seymour

Cromwell’s downfall lent considerably more credence to the authority of the Privy Council. It next met on 10 August 1540 and was dominated by the Henry–Johnites, led by the future King Edward VI’s uncle, Edward Seymour.

Another royal progress to inspect the fortifications at Hull and an abortive meeting with the King of Scotland at York culminated in the young queen’s downfall. The sprightly teenager had committed adultery and was executed; sadly for her, she had merely been a temporary distraction from the improving fortunes of the Seymour strategy.

Within weeks of Catherine Howard’s execution, however, the Seymour enterprise was dealt a blow. The Henry–Johnites’ claim to governance came solely through the young Prince Edward. The bad news, from the Seymour perspective, arrived from Scotland. Mary of Guise was pregnant by James V of Scotland, who was the grandson of Henry VII, founder of the Tudor dynasty. The child, a girl, was born on 8 December 1542. Six days later, her father died and she became Mary Queen of Scots.

With a French mother and the potential for a marriage to French royalty, Mary was a threat to the English monarchy. Indeed, she remained so until she was executed forty-four years later at the behest of Elizabeth I’s Privy Council.

Another royal progress to inspect the fortifications at Hull and an abortive meeting with the King of Scotland at York culminated in the young queen’s downfall. The sprightly teenager had committed adultery and was executed; sadly for her, she had merely been a temporary distraction from the improving fortunes of the Seymour strategy.

Within weeks of Catherine Howard’s execution, however, the Seymour enterprise was dealt a blow. The Henry–Johnites’ claim to governance came solely through the young Prince Edward. The bad news, from the Seymour perspective, arrived from Scotland. Mary of Guise was pregnant by James V of Scotland, who was the grandson of Henry VII, founder of the Tudor dynasty. The child, a girl, was born on 8 December 1542. Six days later, her father died and she became Mary Queen of Scots.

With a French mother and the potential for a marriage to French royalty, Mary was a threat to the English monarchy. Indeed, she remained so until she was executed forty-four years later at the behest of Elizabeth I’s Privy Council.

James V of Scotland and Mary of Guise, Mother and Father of Mary Queen of Scots and Edward Seymour

Deal Then No Deal

Jock

Jock

Leading this present Privy Council, Seymour’s first move in his manoeuvring to prohibit a resurgence of French influence was to claim regal authority for England over Scotland, for which the Treaties of Greenwich were drawn up. The concept was to unite both kingdoms. The first treaty would create peace between the kingdom of England and the kingdom of Scotland. The second would ensure the marriage of the future Edward VI and Mary Queen of Scots. Mary would at first live in Scotland but in the company of an English nobleman and his wife, and then, when she reached the age of ten, she would be removed south to live in England. Later, when she was deemed old enough to marry, she would become Edward’s wife and so unite the two kingdoms.

The Scots returned from Greenwich to Scotland but in no time reneged on the agreement, and so Seymour began a war that became known as the Rough Wooing, an attempt, by force of arms, to coerce the Scots into honouring the treaties and so proceed with the marriage of Edward and Mary.

The Scots returned from Greenwich to Scotland but in no time reneged on the agreement, and so Seymour began a war that became known as the Rough Wooing, an attempt, by force of arms, to coerce the Scots into honouring the treaties and so proceed with the marriage of Edward and Mary.

The Seymour Pimp

Above Images - Jock and the Future Edward VI of England as a Child

Thomas Seymour

Thomas Seymour

The war increased the threat of military intervention from France and the risk of Mary’s extrication there to create a marriage union with the French – as Seymour was attempting with the English royalty.

In anticipation of war, Edward Seymour’s brother, the swashbuckling Thomas, returned from abroad in early 1543. In his view, as the future king’s uncle, he was entitled to as much power and authority as his brother. In an enterprise to secure his place, this ‘man of much wit, and very little judgment’ seduced Katherine Parr, a young but thrice-married lady of the court with a Henry–Johnite ancestry. Fatefully, her third husband died weeks after Thomas’s arrival. Thus, he promised to marry Katherine upon the death of the aged king, but in the meantime he pimped her to Henry VIII. Katherine and Henry were married on 12 July 1543, and accordingly Katherine was installed to marshal the old monarch, on Seymour’s behalf, through his last years.

In anticipation of war, Edward Seymour’s brother, the swashbuckling Thomas, returned from abroad in early 1543. In his view, as the future king’s uncle, he was entitled to as much power and authority as his brother. In an enterprise to secure his place, this ‘man of much wit, and very little judgment’ seduced Katherine Parr, a young but thrice-married lady of the court with a Henry–Johnite ancestry. Fatefully, her third husband died weeks after Thomas’s arrival. Thus, he promised to marry Katherine upon the death of the aged king, but in the meantime he pimped her to Henry VIII. Katherine and Henry were married on 12 July 1543, and accordingly Katherine was installed to marshal the old monarch, on Seymour’s behalf, through his last years.

Boulogne Won - Mary Rose Lost

Above Image - Catherine Parr, Queen of England and Her Lover Thomas Seymour

Sinking of the Mary Rose

Sinking of the Mary Rose

Thomas’s brother Edward meanwhile concentrated on military strategy against the Auld Alliance and a pact was concluded with Charles for a joint Anglo-Imperial invasion of France. Henry insisted on taking part on the pretext that he was reconquering the lost Angevin Empire, despite the physical disabilities he was experiencing.

According to Ambassador Chapuys, Henry by this time ‘had the worst legs in the world’, but nevertheless the king insisted on taking part in the war.

Seymour’s more realistic military aim was to defeat the Scottish threat by cutting off French aid. To achieve this, he set out to capture the port of Boulogne and to set up complete control, together with the English-held Calais, over the Strait of Dover. He succeeded in his aim on 13 September 1544.

Although the French launched a retaliatory attack the following summer (which famously resulted in the loss of the Mary Rose), Francis’s forces were repulsed. England kept an uneasy hold on Boulogne until late spring of 1546, and the Treaty of Ardres was signed on 5 June 1546. The treaty allowed England to keep Boulogne until 1554, by which time – so Seymour hoped – Mary Queen of Scots would be betrothed in a union to his nephew King Edward VI of England and living in a united kingdom of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales.

Above Image - The Sinking of The Mary Rose

Rivals Removed

Stephen Gardiner

Stephen Gardiner

Before he could realise that ambition, however, Seymour had more to accomplish. He needed to facilitate the smooth transfer of power when Henry VIII died, which would require further strategic political manoeuvring.

A dry stamp was introduced in August 1546, which removed the necessity for the king to sign official documents.

As Henry’s health deteriorated, tensions ran high, and John Dudley was suspended from the Privy Council for punching Bishop Gardiner during a meeting.

The conservative faction, including Gardiner, was an obstacle to Seymour’s policy. Gardiner found himself tripped and then fell into a land dispute with Henry. He was consequently excluded from court and his access to the king was blocked. Father and son Thomas and Henry Howard were arrested in mid-December for treason and sent to the Tower. Henry Howard was executed in January.

A dry stamp was introduced in August 1546, which removed the necessity for the king to sign official documents.

As Henry’s health deteriorated, tensions ran high, and John Dudley was suspended from the Privy Council for punching Bishop Gardiner during a meeting.

The conservative faction, including Gardiner, was an obstacle to Seymour’s policy. Gardiner found himself tripped and then fell into a land dispute with Henry. He was consequently excluded from court and his access to the king was blocked. Father and son Thomas and Henry Howard were arrested in mid-December for treason and sent to the Tower. Henry Howard was executed in January.

The End

Above Images - John Dudley and Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester

The path was now clear and, when Henry VIII died on 28 January 1547, the core of the Privy Council (which Seymour had groomed from the ranks of the Henry–Johnites) ratified him as their leader and Lord Protector of the young king – contrary to the deceased king’s deathbed will.

Henry VIII, the Reign, was tumultuous, but few tears were shed for the malleable head of state’s passing. Had he lived, Henry Fitzroy would have succeeded to the throne moulded in the image of the Howards. However, Henry VIII’s surviving offspring were respectively their mothers’ children, products of the diverse politics that dictated the marriages into which the marionette king was cajoled. Edward VI was governed by the forefathers of Oliver Cromwell’s Puritanism, Mary reverted to the Roman Catholicism practised by her mother and Elizabeth then cultivated the middle way conceived from seeds sown by the influence of French kings's sister Marguerite d’Angoulême and Elizabeth’s mother, Anne de Boulogne.

But the surviving children are the subject of later reigns – yet to come.

Henry VIII, the Reign, was tumultuous, but few tears were shed for the malleable head of state’s passing. Had he lived, Henry Fitzroy would have succeeded to the throne moulded in the image of the Howards. However, Henry VIII’s surviving offspring were respectively their mothers’ children, products of the diverse politics that dictated the marriages into which the marionette king was cajoled. Edward VI was governed by the forefathers of Oliver Cromwell’s Puritanism, Mary reverted to the Roman Catholicism practised by her mother and Elizabeth then cultivated the middle way conceived from seeds sown by the influence of French kings's sister Marguerite d’Angoulême and Elizabeth’s mother, Anne de Boulogne.

But the surviving children are the subject of later reigns – yet to come.

Above Images - Henry VIII and Henry VIII with his Fool, Will Somers