Henry VIII, the Reign

Part Twenty - Five

Wolsey’s Deathbed Speech and the Bull of Bologna

Pope Clement VII

Pope Clement VII

|

Bull, notifying that on the appeal of queen Katharine from the judgment of the Legates, who had declared her contumacious for refusing their jurisdiction as being not impartial, the Pope had committed the cause, at her request, to Master Paul Capisucio, the Pope’s chaplain, and auditor of the Apostolic palace, with power to cite the King and others; that the said Auditor, ascertaining that access was not safe, caused the said citation, with an inhibition under censures, and a penalty of 10,000 ducats, to be posted on the doors of the churches in Rome, at Bruges, Tournay, and Dunkirk, and the towns of the diocese of Terouenne (Morinensis). The Queen, however, having complained that the King had boasted, notwithstanding the inhibition and mandate against him, that he would proceed to a second marriage, the Pope issues this inhibition, to be fixed on the doors of the churches as before, under the penalty of the greater excommunication, and interdict to be laid upon the kingdom. Bologna, 7 March 1530, 7 Clement VII. |

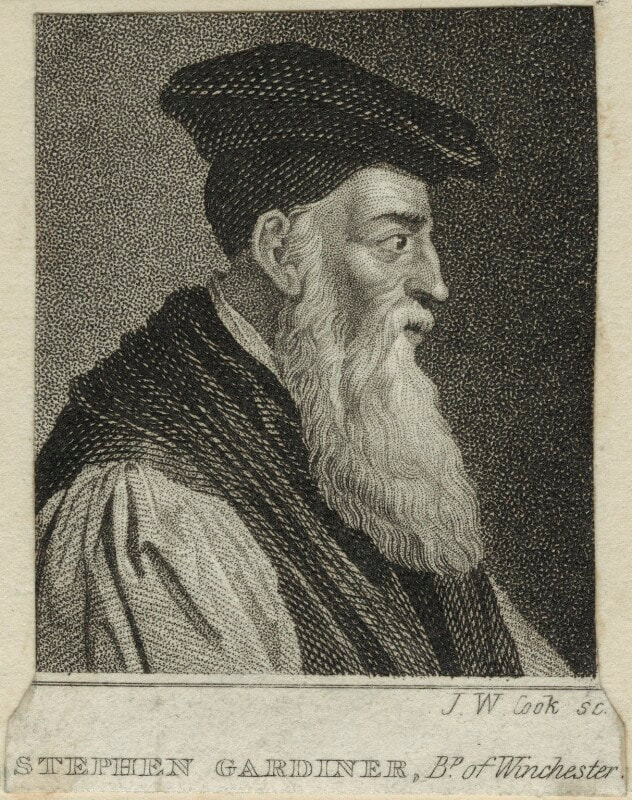

Bishop Stephen Gardiner

Bishop Stephen Gardiner

|

Henry VIII, the Reign.

|

Henry VIII, the Reign.

|