Above: Jane Seymour, Soon to be Henry VIII's Next Wife

Negotiations to Marry Baby Elizabeth into the French Royal Family

Philippe de Chabot

Philippe de Chabot

During 1534, they began negotiations to marry baby Elizabeth into the French royal family, and by the autumn Philippe de Chabot, Admiral de Brion of France, was on his way to England to discuss terms. Chabot arrived during the Parliament sitting. At court, there were anti-French murmurs and mockery of all the flattery, pandering and cowering shown to the French delegation.

Thomas Cromwell, however, was not one of those on bended knee. He was busy entertaining his friends from Germany and exchanging views on their version of Christianity without the pope.

Matters with the French, however, did not go well. They arrived with a proposal that the Dauphin should marry Henry’s oldest daughter, Mary, not Elizabeth. There were doubts in France over Elizabeth’s legitimacy. It was a slur cast upon Anne and her daughter, ‘and the lady [Anne]’, said the Imperial ambassador Eustace Chapuys, ‘is very angry about it’. It was also proposed somewhat maliciously by the emperor that his son should marry Francis’s daughter. If the proposals were intended to upset Anne de Boulogne in an attempt to thwart her desire for the marriage of her daughter Elizabeth to the French, they succeeded.

In November 1534, counter-proposals were drawn up for an alternative marriage arrangement between Francis’s third son (Charles the Duke of Angoulême) and Princess Elizabeth if ‘the French King would obtain from the Bishop of Rome a decision for that the unjust and slanderous sentence given by the late Bishop of Rome is void’; in this event, Henry VIII of England would renounce the title of King of France. With very little agreed, the admiral’s visit ended acrimoniously, and he declined to go to Windsor and other places ‘as the King desired’.

Weeks then passed. Christmas came and went, and still at the beginning of February, the French had sent no response to the English proposals. During this time, Cromwell boasted that he would make his master wealthier than all the other princes in Christendom, which relentlessly undermined the de Boulogne position.

Eventually, after months of silence, Palamedes Gontier, Chabot’s secretary, arrived in England. He was hastily conducted to Westminster. Tensions now ran high; the long delay had fuelled a lack of trust in the French and relations were at a low ebb. Henry interpreted the silence as a snub. He had already spoken to the French ambassador, Charles de Solier, Comte de Morette, so sharply about his countrymen’s conduct that the Frenchman dare not ‘show himself to the King at court’.

Anne de Boulogne also complained mournfully about the long delay, which she said had caused her husband many doubts about her. She was ill at ease and having difficulty maintaining his trust, so reported Gontier. She was living in fear of ruin, she was in more grief and trouble than before her marriage, and she needed help from France before the evangelists trampled over her and the entire country.

The Queen of England was wholly French; she had been mentored by the King of France’s sister Marguerite. The de Boulognes had steered England away from the clutches of the Holy Roman Emperor, and Anne had fulfilled her part in wresting Henry from the emperor’s aunt Catharine of Aragon. She had assured Henry that Francis would be persuaded to take control of the church in France as Henry had done in England, a policy that the de Boulognes were optimistic in believing would gather pace after the death of Pope Clement VII in December 1534.

Thomas Cromwell, however, was not one of those on bended knee. He was busy entertaining his friends from Germany and exchanging views on their version of Christianity without the pope.

Matters with the French, however, did not go well. They arrived with a proposal that the Dauphin should marry Henry’s oldest daughter, Mary, not Elizabeth. There were doubts in France over Elizabeth’s legitimacy. It was a slur cast upon Anne and her daughter, ‘and the lady [Anne]’, said the Imperial ambassador Eustace Chapuys, ‘is very angry about it’. It was also proposed somewhat maliciously by the emperor that his son should marry Francis’s daughter. If the proposals were intended to upset Anne de Boulogne in an attempt to thwart her desire for the marriage of her daughter Elizabeth to the French, they succeeded.

In November 1534, counter-proposals were drawn up for an alternative marriage arrangement between Francis’s third son (Charles the Duke of Angoulême) and Princess Elizabeth if ‘the French King would obtain from the Bishop of Rome a decision for that the unjust and slanderous sentence given by the late Bishop of Rome is void’; in this event, Henry VIII of England would renounce the title of King of France. With very little agreed, the admiral’s visit ended acrimoniously, and he declined to go to Windsor and other places ‘as the King desired’.

Weeks then passed. Christmas came and went, and still at the beginning of February, the French had sent no response to the English proposals. During this time, Cromwell boasted that he would make his master wealthier than all the other princes in Christendom, which relentlessly undermined the de Boulogne position.

Eventually, after months of silence, Palamedes Gontier, Chabot’s secretary, arrived in England. He was hastily conducted to Westminster. Tensions now ran high; the long delay had fuelled a lack of trust in the French and relations were at a low ebb. Henry interpreted the silence as a snub. He had already spoken to the French ambassador, Charles de Solier, Comte de Morette, so sharply about his countrymen’s conduct that the Frenchman dare not ‘show himself to the King at court’.

Anne de Boulogne also complained mournfully about the long delay, which she said had caused her husband many doubts about her. She was ill at ease and having difficulty maintaining his trust, so reported Gontier. She was living in fear of ruin, she was in more grief and trouble than before her marriage, and she needed help from France before the evangelists trampled over her and the entire country.

The Queen of England was wholly French; she had been mentored by the King of France’s sister Marguerite. The de Boulognes had steered England away from the clutches of the Holy Roman Emperor, and Anne had fulfilled her part in wresting Henry from the emperor’s aunt Catharine of Aragon. She had assured Henry that Francis would be persuaded to take control of the church in France as Henry had done in England, a policy that the de Boulognes were optimistic in believing would gather pace after the death of Pope Clement VII in December 1534.

Anne de Boulogne -

'Now she was more vulnerable than she had been before she was married'

Anne had been offered up as bait for Henry when the French were desperate for English help to have Francis released from Spain. However, those days were long gone. Increasingly isolated, her position was ever weakening; she clung to the ambition to unite the reigning Valois of France with her daughter Elizabeth, who was of de Boulogne blood, but many of those who counselled Henry filled his head with pro-Lutheran and anti-French sentiment. Now she was more vulnerable than she had been before she was married. Her daughter’s marriage was vital to secure her future before the Francophobes wrenched the royal sanction from her grasp.

As winter turned to spring, negotiations continued, but the French were deserting Anne. Still, Francis wanted to know: if Mary were one day successful in her claim of legitimacy and did succeed to the throne of England, what state then would the marriage between Elizabeth and his son the duke be in?

As winter turned to spring, negotiations continued, but the French were deserting Anne. Still, Francis wanted to know: if Mary were one day successful in her claim of legitimacy and did succeed to the throne of England, what state then would the marriage between Elizabeth and his son the duke be in?

Henry continued to reject a union with Mary. If there were to be a marriage, it

would be with Elizabeth. He wrote thus to Chabot:

|

Both by the King our brother’s letters and yours we feel assured of his desire to preserve the amity between us to our successors; and though we cannot agree to the propositions made by the treasurer Palamedes, our reasons for declining them are such as you yourself will see to be right. As to the marriage proposed, as we were the first inventor of that knot, we purpose to send shortly to Calais deputies for our part, viz., the duke of Norfolk. Fitzwilliam and Cromwell, to arrange the conditions.

The most convenient time for the meeting at Calais is about Whitsuntide next, not sooner, that Francis may have an opportunity of using his great influence with the bishop of Rome that he may revoke the sentence of his predecessor Clement about the pretended marriage with the lady Katharine. and declare it naught; which should be easy, as we find the opinion of the learned men about the Pope agrees with ours, and that he himself is somewhat disposed that way. But if the said Bishop follow the steps of his predecessor, we trust our good brother, considering the decision of his own universities and of Christendom, will adhere to us; and, meantime, that he will not practise either by marriage or otherwise with the Emperor or the king of Portugal. When we know our good brother’s determination on these points, we shall send our said deputies at Whitsuntide. |

Cromwell, who when the time came did not go to Calais, was working in an entirely different direction, edging closer to an alliance with the Germans. He was also planning the 1535 summer royal progress to the west country.

The negotiations with the French failed.

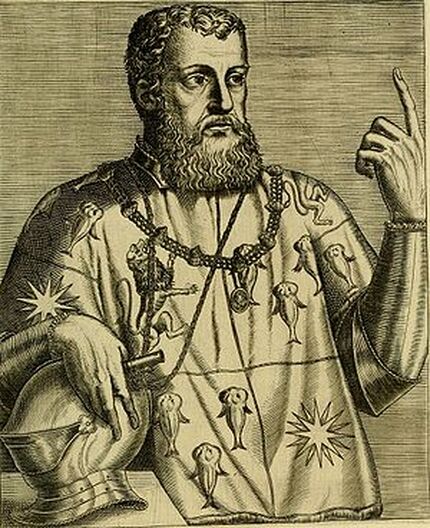

Francis Dauphin of France

Francis Dauphin of France

Anne’s brother George de Boulogne, Viscount Rochford, went to Calais at Whitsun in place of Cromwell. He carried with him an English stipulation, fatal to Boulogne ambitions, for the young French duke to be educated in England. Francis was furious about the audacity of that suggestion. Cromwell, he perceived, had inserted a clause to hold his son hostage. Hadn’t his brothers suffered enough incarcerated as hostages in Spain by Charles a decade earlier?

Cromwell, however, had every reason to hold his ground. The duke’s eldest brother, the Dauphin, had boasted from the rooftops that he ‘would regain the title and arms which the king of England bore and that he would succeed where the Dauphin Prince Louis had failed in the time of King John’.

Cromwell, however, had every reason to hold his ground. The duke’s eldest brother, the Dauphin, had boasted from the rooftops that he ‘would regain the title and arms which the king of England bore and that he would succeed where the Dauphin Prince Louis had failed in the time of King John’.

A ‘thousand shameful words’ of the King of France,

and generally the whole nation.

With Francis fuming, Rochford broke from the interview and returned to England desperate for alternative instructions, but first, he was a long-time consulting with his sister about their impending predicament. Anne, according to Chapuys, had been in bad humour and said a ‘thousand shameful words’ of the King of France, and generally the whole nation.

Cromwell held Rochford back from making a swift return to Calais. The negotiations collapsed, and at the same time, Cromwell continued to consult with the Germans.

According to Chapuys, on 2 June Anne, as her fortunes crumbled, admonished Cromwell and wished she could see his head cut off.

Within a year this fate would become hers instead – but while she still lived there was worse to come – soon she would leave Windsor and travel on the 1535 Royal Progress.

The Cromwellian regime was taking over, the king’s entourage was heading to Seymour country for the 1535 season, it was to be spent, ‘riding under the louring skies and foliage of an unusually wet summer.’

It was to be Anne de Boulogne’s last.

Cromwell held Rochford back from making a swift return to Calais. The negotiations collapsed, and at the same time, Cromwell continued to consult with the Germans.

According to Chapuys, on 2 June Anne, as her fortunes crumbled, admonished Cromwell and wished she could see his head cut off.

Within a year this fate would become hers instead – but while she still lived there was worse to come – soon she would leave Windsor and travel on the 1535 Royal Progress.

The Cromwellian regime was taking over, the king’s entourage was heading to Seymour country for the 1535 season, it was to be spent, ‘riding under the louring skies and foliage of an unusually wet summer.’

It was to be Anne de Boulogne’s last.

|

The man on the left is bound for Winchester

|