Henry VIII, the Reign - Holinshed's Articles

By Mark Holinshed

The Royal Progress - Berkeley Castle to Thornbury Castle

Henry VIII is in the Welsh Marches

|

“The King is still on the confines of Wales, [the Welsh Marches] hunting and traversing the country to gain the people. It is said many of the peasants where he has passed, hearing the preachers who follow the Court, are so much abused as to believe that God has inspired the King to separate himself from the wife of his brother; but these are mere "idiotes," who will soon return to the truth when there is any appearance of remedy. The Queen and Princess are well and continually pray for your prosperity. London, 10 Aug. 1535.” |

Thomas Cromwell, Joint Constable of Berkeley Castle with his Nephew Richard Williams

Thomas Cromwell, Joint Constable of Berkeley Castle with his Nephew Richard Williams

So said the Imperial Ambassador, Eustace Chapuys when writing to Charles V on 10 August.

The royal entourage arrived at Berkeley Castle on 7 August, but although most of the officials of his court along with his cantankerous queen were there, the king it seems was not.

But why would he be?

Henry VIII was not one for official business, he was one for the outdoors and hunting, the thrill of the chase. In this area he was spoilt for choice, he was off – hunting gear and all, to whichever forest took him, and his cohorts fancy.

A person who was not with him, unless he had sneaked him along, was his fool, the court jester, Will Sommers. Anne de Boulogne had banished Will from the court for calling her a ‘Ribaude’ and Princess Elizabeth a ‘bastard’. Sommers fled, in fear of his life, and was taken into the household of Sir Nicholas Carew.

Berkeley Castle had been a crown property since 1492, when William de Berkeley, 1st Marquess of Berkeley disinherited his brother Maurice.

Maurice had married Isabel Meade, who William considered to be below the Berkeley’s social status.

William the Waste-All, as he became known, then settled the castle, lands and lordships including the Barony of Berkeley, on King Henry VII and his male heirs, the last of which was Edward VI who died in 1553.

At the time of the 1535 royal progress, Thomas Cromwell was joint constable of the castle with his Welsh-born nephew, his sister Katherine’s son, Richard Williams. Williams was Oliver Cromwell’s great grandfather.

The royal entourage arrived at Berkeley Castle on 7 August, but although most of the officials of his court along with his cantankerous queen were there, the king it seems was not.

But why would he be?

Henry VIII was not one for official business, he was one for the outdoors and hunting, the thrill of the chase. In this area he was spoilt for choice, he was off – hunting gear and all, to whichever forest took him, and his cohorts fancy.

A person who was not with him, unless he had sneaked him along, was his fool, the court jester, Will Sommers. Anne de Boulogne had banished Will from the court for calling her a ‘Ribaude’ and Princess Elizabeth a ‘bastard’. Sommers fled, in fear of his life, and was taken into the household of Sir Nicholas Carew.

Berkeley Castle had been a crown property since 1492, when William de Berkeley, 1st Marquess of Berkeley disinherited his brother Maurice.

Maurice had married Isabel Meade, who William considered to be below the Berkeley’s social status.

William the Waste-All, as he became known, then settled the castle, lands and lordships including the Barony of Berkeley, on King Henry VII and his male heirs, the last of which was Edward VI who died in 1553.

At the time of the 1535 royal progress, Thomas Cromwell was joint constable of the castle with his Welsh-born nephew, his sister Katherine’s son, Richard Williams. Williams was Oliver Cromwell’s great grandfather.

The Berkeleys of Berkeley Castle were Not the Original Berkeleys

The first Berkeleys of Berkeley Castle were also Lords of Dursley, Leonard Stanley, Dodington and various other possessions in England and Wales.

During the Anarchy, this line of Berkeleys took the side of King Stephen and his son Eustace de Boulogne against Robert of Gloucester. Roger’s nephew Henry II was the eventual victor in the civil war, and consequently, the original Berkeleys of Berkeley were dispossessed. The lands were granted the estates to an ardent supporter of Henry’s during the conflict, the wealthy Robert Fitz Harding of Bristol.

The Berkeleys, however, defied the move, they would not budge from the castle and held it by force.

A compromise was thrashed through; the Berkeleys of Dursley retained Dursley, Dodington and Leonard Stanley on the condition that they gave up the wealthiest barony, Berkeley, to the Fitzhardings – which they did, and when so doing two intermarriages of the families were negotiated, probably by Henry.

Over the following years, the Fitzharding de Berkeley line dropped the use of the Fitz Harding name, but it is that line of descent that survives there today and not the original Berkeleys.

During the Anarchy, this line of Berkeleys took the side of King Stephen and his son Eustace de Boulogne against Robert of Gloucester. Roger’s nephew Henry II was the eventual victor in the civil war, and consequently, the original Berkeleys of Berkeley were dispossessed. The lands were granted the estates to an ardent supporter of Henry’s during the conflict, the wealthy Robert Fitz Harding of Bristol.

The Berkeleys, however, defied the move, they would not budge from the castle and held it by force.

A compromise was thrashed through; the Berkeleys of Dursley retained Dursley, Dodington and Leonard Stanley on the condition that they gave up the wealthiest barony, Berkeley, to the Fitzhardings – which they did, and when so doing two intermarriages of the families were negotiated, probably by Henry.

Over the following years, the Fitzharding de Berkeley line dropped the use of the Fitz Harding name, but it is that line of descent that survives there today and not the original Berkeleys.

Wykes! – There’s More

The Berkeley of Dursley line continued down ‘from father to son in regular succession until the year 1382, when the last son of the line died without children.’

By 1535 the holdings of the original Berkeleys of Dursley had come down by marriage to the Wykes family, and as mentioned in the previous post, Wykes was Thomas Cromwell’s wife Elizabeth’s maiden name.

Cromwell himself by this time was receiving a constant flow of reports from the commissioners that he had appointed to visit and investigate the monasteries prior to the wholesale closure that would follow shortly.

By 1535 the holdings of the original Berkeleys of Dursley had come down by marriage to the Wykes family, and as mentioned in the previous post, Wykes was Thomas Cromwell’s wife Elizabeth’s maiden name.

Cromwell himself by this time was receiving a constant flow of reports from the commissioners that he had appointed to visit and investigate the monasteries prior to the wholesale closure that would follow shortly.

Berkeley Castle to Thornbury Castle

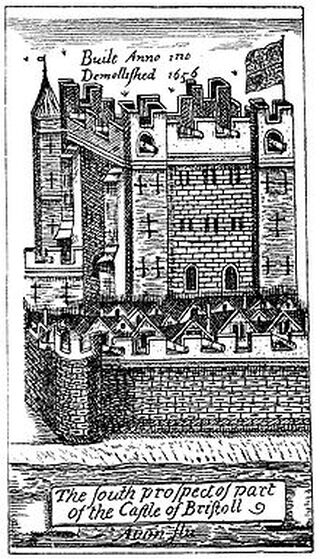

Bristol Castle - But the Visit was Off

Bristol Castle - But the Visit was Off

14 August 1535

Berkley Castle to Thornbury Castle is a short trip, about seven miles, the Roman Road that continues towards Bristol is straight and flat. It is probable, given the size of a royal progress, and that the two castles are so close that both were used at the same time for lodgings.

Bristol, it had been planned from the outset, should have been the furthers extremity of the tour, before turning for the long journey home – there would be another nine weeks or so on the road yet. Bristol was ‘Western Capital of England’ and so the capital of the Brittonic – English cause, Cromwell held high office there as recorder.

In August 1535, however, there was plague at Bristol, and the visit was cancelled.

With the Bristol visit off the ‘outdoor’ king would have been at a loose end, but he had his hunting boots with him, and so if he ever did get to Thornbury at all, it was probably as the entourage was leaving for Acton Court.

Indeed, Ambassador Chapuys sent ‘his man’ from London with a message for the king and after some tarrying, ‘at last it was arranged that he should be in the fields where the duke of Norfolk and Suffolk and Cromwell went to hunt.’ Where those fields were, unfortunately, Chapuys does not tell us.

Berkley Castle to Thornbury Castle is a short trip, about seven miles, the Roman Road that continues towards Bristol is straight and flat. It is probable, given the size of a royal progress, and that the two castles are so close that both were used at the same time for lodgings.

Bristol, it had been planned from the outset, should have been the furthers extremity of the tour, before turning for the long journey home – there would be another nine weeks or so on the road yet. Bristol was ‘Western Capital of England’ and so the capital of the Brittonic – English cause, Cromwell held high office there as recorder.

In August 1535, however, there was plague at Bristol, and the visit was cancelled.

With the Bristol visit off the ‘outdoor’ king would have been at a loose end, but he had his hunting boots with him, and so if he ever did get to Thornbury at all, it was probably as the entourage was leaving for Acton Court.

Indeed, Ambassador Chapuys sent ‘his man’ from London with a message for the king and after some tarrying, ‘at last it was arranged that he should be in the fields where the duke of Norfolk and Suffolk and Cromwell went to hunt.’ Where those fields were, unfortunately, Chapuys does not tell us.

Thornbury Castle – Albeit in the Kings Absence

Enemies - Wolsey and Buckingham

Enemies - Wolsey and Buckingham

Since before the conquest there had been a manor house on the site of Thornbury Castle.

In 1535 Thornbury Castle was a crown property, lost by its previous owner Edward Stafford Duke of Buckingham in 1521. The Duke at that time was advanced in an ambitious rebuilding of Thornbury, which unfortunately for him he did not live to see finished.

By descent from Edward III’s son Thomas of Woodstock he had a claim to the throne, possibly as strong as the Tudors, and accusations of disloyalty to Henry VIII found their way into cliques in court circles. Gossip, innuendo and intrigue circulated the corridors until the duke found himself on trial before a panel of seventeen peers. He was accused of listening to prophecies of the King's death and intending to kill the King.

Buckingham was executed on Tower Hill on 17 May and posthumously attainted by Act of Parliament on 31 July 1523.

Stafford was famously a bitter enemy of Thomas Wolsey and the cardinal’s domination of the malleable young king, and it was probably the clergyman that brought about his downfall.

In 1535, for these weeks in August, Thornbury Castle was officially the seat of government. William Paulet, Comptroller of the Household, was a busy man, and the castle’s hundreds of rooms hosted a bustling surfeit of bureaucrats, droll court entertainers, eager hunting parties and harried victuallers – the kingdom’s policymakers were also hard at work.

In 1535 Thornbury Castle was a crown property, lost by its previous owner Edward Stafford Duke of Buckingham in 1521. The Duke at that time was advanced in an ambitious rebuilding of Thornbury, which unfortunately for him he did not live to see finished.

By descent from Edward III’s son Thomas of Woodstock he had a claim to the throne, possibly as strong as the Tudors, and accusations of disloyalty to Henry VIII found their way into cliques in court circles. Gossip, innuendo and intrigue circulated the corridors until the duke found himself on trial before a panel of seventeen peers. He was accused of listening to prophecies of the King's death and intending to kill the King.

Buckingham was executed on Tower Hill on 17 May and posthumously attainted by Act of Parliament on 31 July 1523.

Stafford was famously a bitter enemy of Thomas Wolsey and the cardinal’s domination of the malleable young king, and it was probably the clergyman that brought about his downfall.

In 1535, for these weeks in August, Thornbury Castle was officially the seat of government. William Paulet, Comptroller of the Household, was a busy man, and the castle’s hundreds of rooms hosted a bustling surfeit of bureaucrats, droll court entertainers, eager hunting parties and harried victuallers – the kingdom’s policymakers were also hard at work.

Was the king ever at Thornbury?

Worcester - the Prior was in Trouble

Worcester - the Prior was in Trouble

Chapuys has already told us that he had spent time in the Welsh Marches and in a field somewhere. On 20 August he was over sixty miles north at Beawdley or as we know it today Bewdley, on the River Severn. From there he had written to the Abbott of Saint Austin’s of Bristol ‘commanding him to pluck up the weirs in the Severne that the King may be advertised of it before his departure from Thornbury.’

The weirs that Henry wanted plucking up were essentially fish traps, ‘artificial barriers of stone or wood built in rivers or estuaries to deflect fish into an opening where they could be trapped in nets or baskets.’ Shad and Herring were among the fish that the weirs trapped, and such fish were a meal kings and queens savoured. Some years later, Henry’s daughter Elizabeth ordered the destruction of weirs to prevent the taking of ‘any lamprey, shad or Twaite’.

On 17 August, the post had arrived, probably at Bewdley, and with it a packet of letters which Cromwell opened and read before he laid them before the king, they were from Sir John Wallop, the Ambassador of the Kingdom of England to France. It seems that Cromwell was also up at Bewdley dealing with Rowland Lee, Bishop of Coventry and Litchfield, over allegations of impropriety against William More the Prior of Worcester.

The weirs that Henry wanted plucking up were essentially fish traps, ‘artificial barriers of stone or wood built in rivers or estuaries to deflect fish into an opening where they could be trapped in nets or baskets.’ Shad and Herring were among the fish that the weirs trapped, and such fish were a meal kings and queens savoured. Some years later, Henry’s daughter Elizabeth ordered the destruction of weirs to prevent the taking of ‘any lamprey, shad or Twaite’.

On 17 August, the post had arrived, probably at Bewdley, and with it a packet of letters which Cromwell opened and read before he laid them before the king, they were from Sir John Wallop, the Ambassador of the Kingdom of England to France. It seems that Cromwell was also up at Bewdley dealing with Rowland Lee, Bishop of Coventry and Litchfield, over allegations of impropriety against William More the Prior of Worcester.

The Fruits of a Strategy

Anne de Boulogne

Anne de Boulogne

The correspondence from Wallop was about the executions of Thomas More and John Fisher a few weeks earlier, the news of which had by now spread across Christendom. Wallop detailed Francis King of France’s criticism of Henry over the deaths.

The criticism riled Henry, he was still sore with Francis for what he perceived as broken promises by the French king to take Henry’s side against the pope in his quest for a divorce.

Back in July 1533, Henry had been threatened by the pope with excommunication if he did not take back Catherine of Aragon, which of course he had not, and if Francis persisted in censuring him over the More and Fisher executions, there was a real possibility that the threat of excommunication would become a reality.

This, however, was what the Cromwell – Seymour faction was playing for. It was a part of their strategy, which was now bearing fruit, to wrest control from the de Boulognes. In their scheme, the execution of the Carthusian monks and the deaths of More and Fisher would trigger a furious reaction from Rome, force the pope to act and excommunicate Henry and so sever their monarch’s personal and heartfelt connection with the office of the pope. It would also create a rift between English and French kings.

England would be rid of the pope and the interference of France in the English government, propagated by Anne de Boulogne.

The criticism riled Henry, he was still sore with Francis for what he perceived as broken promises by the French king to take Henry’s side against the pope in his quest for a divorce.

Back in July 1533, Henry had been threatened by the pope with excommunication if he did not take back Catherine of Aragon, which of course he had not, and if Francis persisted in censuring him over the More and Fisher executions, there was a real possibility that the threat of excommunication would become a reality.

This, however, was what the Cromwell – Seymour faction was playing for. It was a part of their strategy, which was now bearing fruit, to wrest control from the de Boulognes. In their scheme, the execution of the Carthusian monks and the deaths of More and Fisher would trigger a furious reaction from Rome, force the pope to act and excommunicate Henry and so sever their monarch’s personal and heartfelt connection with the office of the pope. It would also create a rift between English and French kings.

England would be rid of the pope and the interference of France in the English government, propagated by Anne de Boulogne.

Cromwell Pens a Rebuke to the King of France

From Thornbury, on 23 August 1535 Cromwell wrote his reply to Wallop with a rebuke to be conveyed to the French.

|

"The King thanks him for his conduct of the demand for the pensions from the French king, and sends instructions as follows:--

Since the French king and the Great Master have promised that the pensions shall be despatched, he is to continue to call till they be sent. Concerning the French king's assurance that he has always answered for the King, especially at Marseilles with Pope Clement, and also concerning the late executions in England:—In the first, he is to tell the French king, or at least the Great Master, that since the King's rule is based on God's law, and requires no defence, Francis has merely acted the part of a brother "in justifying and verifying the truth." In the second, Mr. More and the bishop of Rochester, and the others who were executed, were lawfully convicted and deservedly punished for high treason. He is to procure the copy promised him by the Great Master, of the French king's information as to the sayings of Mr. More to his daughter and to the people at his execution "(assuring you that there was no such thing)." The King cannot but take it unkindly that Francis should so lightly give credence to "vayne bruts and fleeng tales." The laws the King has made in England have been maturely deliberated. They are not new, but only renovated and renewed. Since Francis has confessed his intention to recall such as he has banished for speaking against the Pope, it is not the office of a friend or brother to advise Henry to banish his traitors into foreign lands, where they may have opportunity to work their feats of treason." |

Stuff for The Birds

We have seen in a previous post that the wholly French Anne de Boulogne, back in March 1535 was '…more vulnerable than she had been before she was married'. Now her position was weakened even further.

And so, encouragement to 'Spend the night in Henry VIII's honeymoon suite in a 10th century Tudor castle', and such like, is frankly, stuff for the birds.

And so, encouragement to 'Spend the night in Henry VIII's honeymoon suite in a 10th century Tudor castle', and such like, is frankly, stuff for the birds.