Henry VIII, the Reign - Holinshed's Articles

By Mark Holinshed

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, the Papa of

Christendom

His Maritime Spectacular

By the end of 1519, there were three; the aged Maximilian died, and the enormous Holy Roman Empire was enjoined with the Kingdom of Spain and ruled by Charles. This new order, with Charles at its head geographically surrounded the Kingdom of France – except of course, for the coast line with the Strait of Dover, which significantly, throughout history, has separated it from England.

Three young sovereigns governed Christendom, Charles 19 years old, Francis 24 and Henry 28, they were influenced, according to his prevailing strength, by the pope.

English Cardinal Legate Thomas Wolsey, the pope’s second persona, however, as self-appointed Papa to the three, fancied he could run all of Christendom and rebuild the papacy to emulate the like of Pope Innocent III. He set about doing just that.

Charles V, the King of Spain, was elected Holy Roman Emperor in 1519 by a unanimous vote, defeating his principle rival Francis I, the King of France. The effect of his election was to unite the territories Charles had inherited from his maternal grandfather, Ferdinand, with those of his paternal grandfather, Maximilian, in the name of Habsburg. For the rest of their lives, Valois Francis and Habsburg Charles would be bitter enemies.

The ceremony for the coronation of the Holy Roman Emperor, established over many centuries, was a series of rituals, the first of which took place in Aachen, in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. This presented some difficulties for Charles because at the time of his election he lived in Spain.

By the end of 1519, there were three; the aged Maximilian died, and the enormous Holy Roman Empire was enjoined with the Kingdom of Spain and ruled by Charles. This new order, with Charles at its head geographically surrounded the Kingdom of France – except of course, for the coast line with the Strait of Dover, which significantly, throughout history, has separated it from England.

Three young sovereigns governed Christendom, Charles 19 years old, Francis 24 and Henry 28, they were influenced, according to his prevailing strength, by the pope.

English Cardinal Legate Thomas Wolsey, the pope’s second persona, however, as self-appointed Papa to the three, fancied he could run all of Christendom and rebuild the papacy to emulate the like of Pope Innocent III. He set about doing just that.

Charles V, the King of Spain, was elected Holy Roman Emperor in 1519 by a unanimous vote, defeating his principle rival Francis I, the King of France. The effect of his election was to unite the territories Charles had inherited from his maternal grandfather, Ferdinand, with those of his paternal grandfather, Maximilian, in the name of Habsburg. For the rest of their lives, Valois Francis and Habsburg Charles would be bitter enemies.

The ceremony for the coronation of the Holy Roman Emperor, established over many centuries, was a series of rituals, the first of which took place in Aachen, in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. This presented some difficulties for Charles because at the time of his election he lived in Spain.

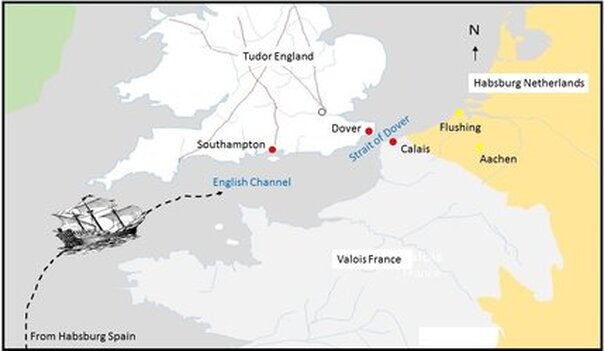

The English Channel and the Imperial Crown

There was peace in Europe in 1519 because the Treaty of London, organised in 1518 by Thomas Wolsey, Cardinal Archbishop of York and Papal Legate, had been upheld. Any peace, however, between the Habsburg and Valois dynasties was fragile and was likely to be broken at any moment. Francis held military sway in northern Italy but Charles needed to establish communications between his vast territories now united under one sceptre in Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain. There were two alternative routes, either through the Strait of Dover to the port of Flushing (Vlissingen) in the Netherlands or from Barcelona to Genoa and then through Millan to the Tyrol. Innsbruck to Aachen, however, was still another 450 miles overland, and by going that way he would always be vulnerable to attack from France, and in the Mediterranean he would also be threatened by the Turks.

Any French threat in the Strait of Dover, however, could be parried by the alliance with England, which was sealed by his aunt Catherine of Aragon’s marriage to Henry VIII. England possessed a powerful navy, and Uncle Henry would be flattered to be the first monarch to receive the Holy Roman Emperor elect as a guest. The original plan was for Charles to disembark at Southampton and travel overland, meeting up again with his ships at Dover, re-embarking there and so avoiding the Strait of Dover altogether.

Cardinal Wolsey placed himself in charge of the arrangements on the English side.

There was peace in Europe in 1519 because the Treaty of London, organised in 1518 by Thomas Wolsey, Cardinal Archbishop of York and Papal Legate, had been upheld. Any peace, however, between the Habsburg and Valois dynasties was fragile and was likely to be broken at any moment. Francis held military sway in northern Italy but Charles needed to establish communications between his vast territories now united under one sceptre in Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain. There were two alternative routes, either through the Strait of Dover to the port of Flushing (Vlissingen) in the Netherlands or from Barcelona to Genoa and then through Millan to the Tyrol. Innsbruck to Aachen, however, was still another 450 miles overland, and by going that way he would always be vulnerable to attack from France, and in the Mediterranean he would also be threatened by the Turks.

Any French threat in the Strait of Dover, however, could be parried by the alliance with England, which was sealed by his aunt Catherine of Aragon’s marriage to Henry VIII. England possessed a powerful navy, and Uncle Henry would be flattered to be the first monarch to receive the Holy Roman Emperor elect as a guest. The original plan was for Charles to disembark at Southampton and travel overland, meeting up again with his ships at Dover, re-embarking there and so avoiding the Strait of Dover altogether.

Cardinal Wolsey placed himself in charge of the arrangements on the English side.

A painting which shows Henry VIII and his fleet setting sail from Dover to Calais on 31 May 1520 on the way to meet Francis I at The Field of Cloth of Gold. Henry VIII is shown standing on one of the vessel with golden sails in the background.

A painting which shows Henry VIII and his fleet setting sail from Dover to Calais on 31 May 1520 on the way to meet Francis I at The Field of Cloth of Gold. Henry VIII is shown standing on one of the vessel with golden sails in the background.

Wolsey’s Balancing Act

For the time being, England was pivotal in the balance of power between Valois France on the one side and the expanding Habsburg Empire on the other. The infinitely ambitious Wolsey had by this time appointed himself as a sort of steward of Christendom, the wise man presiding over the three inexperienced young monarchs, Charles, aged nineteen, Francis, twenty-four and Henry, twenty-eight.

Wolsey’s career with Henry VIII had begun with him as the youthful king’s almoner; he was then promoted to be Bishop of Lincoln, and after that very quickly became the Archbishop of York, then Cardinal Archbishop and then the Papal Legate in England. Now he was after the top job, the papacy itself.

Charles set sail from La Carruna and left Adrian of Utrecht, his former tutor and adviser in the Netherlands, with the daunting task of administering the kingdom of Spain as regent during his absence. Adrian had been a senior administrator in Spain since 1515.

Wolsey, as Charles sailed north, was erring towards the French and King Francis for support in relation to his aspirations to become pope. In return, he pledged England’s political and military assistance to France with the intention of tipping the balance of power in favour of the Valois dynasty over the Hapsburgs, but Wolsey was always open to an improved arrangement.

For the time being, England was pivotal in the balance of power between Valois France on the one side and the expanding Habsburg Empire on the other. The infinitely ambitious Wolsey had by this time appointed himself as a sort of steward of Christendom, the wise man presiding over the three inexperienced young monarchs, Charles, aged nineteen, Francis, twenty-four and Henry, twenty-eight.

Wolsey’s career with Henry VIII had begun with him as the youthful king’s almoner; he was then promoted to be Bishop of Lincoln, and after that very quickly became the Archbishop of York, then Cardinal Archbishop and then the Papal Legate in England. Now he was after the top job, the papacy itself.

Charles set sail from La Carruna and left Adrian of Utrecht, his former tutor and adviser in the Netherlands, with the daunting task of administering the kingdom of Spain as regent during his absence. Adrian had been a senior administrator in Spain since 1515.

Wolsey, as Charles sailed north, was erring towards the French and King Francis for support in relation to his aspirations to become pope. In return, he pledged England’s political and military assistance to France with the intention of tipping the balance of power in favour of the Valois dynasty over the Hapsburgs, but Wolsey was always open to an improved arrangement.

The Field of the Cloth of Gold

The Field of the Cloth of Gold

The Field of the Cloth of Gold

The French king and Henry VIII had often expressed a desire to meet each other and so Wolsey arranged an outlandishly lavish event that became known as the Field of the Cloth of Gold, infamous for its glamour, extravagance and apparent lack of political significance.

Francis, at some point during it all, beat Henry at wrestling, which is about as interesting as it got, except for Wolsey’s stock.

Anyway, the staging of such an event was a logistical marvel in its day and would still be a remarkable achievement today. The total number of Henry’s company for the revels was estimated at 4,000 people and over 2,000 horses and Queen Catherine’s at over 1,000 people and more than 750 horses. There were dukes and earls, bishops, barons and a marquis, together with an army of priests. Then there were tents, timber for buildings, costumes for revels, the king’s bed, all the paraphernalia for the jousting, marvellous statues of ancient princes, probably a kitchen sink or two, and so on and so on. All this was shipped across to France by the splendid power of the English navy.

Charles made good time from Spain and, rather than land at Southampton, Wolsey rowed out to meet him, and for his trouble Charles granted him the financial rewards of an entire Spanish bishopric and the substantial part of the revenues of another.

On Whit Sunday, 27 May 1520, Charles rode at the head of a procession from Dover to Canterbury, where the great royal meeting took place and Henry VIII and Queen Catherine embraced their nephew for the first time. Over the next few days, some treaties were signed and then Charles rode back to Dover and sailed on to Flushing while Henry and Wolsey headed to Calais and then on to the jolly in the field.

After the Field of Cloth of Gold, Henry and Wolsey met Charles again at Gravelines, a few miles north of Calais.

All had gone safely for Charles, and he was crowned with the Iron Crown of Lombardy in the great cathedral of Charlemagne in Aachen on 23 July 1520.The emperor was grateful for the part Wolsey had played in his secure arrival and must have thought sailing back to Spain from the Netherlands, if matters were arranged and managed with the same efficiency as the outward journey, would be a breeze.

Back to War

However, soon after Charles was crowned, the peace with France that had held since 1518 was shattered. By the spring of 1521, fighting had broken out in both Luxemburg and Navarre. Each side blamed the other. Accusations flew on one side that the Valois dynasty had started it and on the other side that the Habsburg dynasty had started it; it was even rumoured that some third party had started it. For Charles, who needed to get back to Spain, this was a dangerous situation.

For Wolsey, the arch negotiator, the resulting situation could not have been more convenient if he had engineered it himself. Charles was stuck in the Netherlands when he soon needed to be in Spain but he would be in mortal danger if he left by either land or sea.

Calais, Bruges and Double-Dealing

Wolsey was soon in action: he pulled on his arbiter’s hat, marshalled his great entourage, which included Thomas Ruthall, Cuthbert Tunstall and Thomas More, and set off across the Channel, arriving at Calais on 2 August 1522. The fighting continued unabated, and ostensibly he was there to direct a peace conference. The first session was held on 7 August, and the Habsburg and Valois representatives were present. Charles waited on safe territory in Bruges, from where he wrote to Wolsey and asked the cardinal to go and meet him there.

In response, Wolsey, supposedly the impartial mediator, bluffed the French and went off to meet the emperor in Bruges, where they negotiated a treaty to their own advantage but excluding and to the detriment of the French. The treaty contracted Charles to a future marriage with Henry’s daughter Princess Mary; she was five at the time and of course the marriage never happened.

Beyond all the marriage stipulations, however, most of the remainder of the treaty dealt with Charles’s return to Spain the following spring and the protection he would receive on the journey from the English navy. The return was to be coordinated with a joint, simultaneous declaration of war against France. Wolsey agreed to all this and in return Charles promised to make him pope.

The French king and Henry VIII had often expressed a desire to meet each other and so Wolsey arranged an outlandishly lavish event that became known as the Field of the Cloth of Gold, infamous for its glamour, extravagance and apparent lack of political significance.

Francis, at some point during it all, beat Henry at wrestling, which is about as interesting as it got, except for Wolsey’s stock.

Anyway, the staging of such an event was a logistical marvel in its day and would still be a remarkable achievement today. The total number of Henry’s company for the revels was estimated at 4,000 people and over 2,000 horses and Queen Catherine’s at over 1,000 people and more than 750 horses. There were dukes and earls, bishops, barons and a marquis, together with an army of priests. Then there were tents, timber for buildings, costumes for revels, the king’s bed, all the paraphernalia for the jousting, marvellous statues of ancient princes, probably a kitchen sink or two, and so on and so on. All this was shipped across to France by the splendid power of the English navy.

Charles made good time from Spain and, rather than land at Southampton, Wolsey rowed out to meet him, and for his trouble Charles granted him the financial rewards of an entire Spanish bishopric and the substantial part of the revenues of another.

On Whit Sunday, 27 May 1520, Charles rode at the head of a procession from Dover to Canterbury, where the great royal meeting took place and Henry VIII and Queen Catherine embraced their nephew for the first time. Over the next few days, some treaties were signed and then Charles rode back to Dover and sailed on to Flushing while Henry and Wolsey headed to Calais and then on to the jolly in the field.

After the Field of Cloth of Gold, Henry and Wolsey met Charles again at Gravelines, a few miles north of Calais.

All had gone safely for Charles, and he was crowned with the Iron Crown of Lombardy in the great cathedral of Charlemagne in Aachen on 23 July 1520.The emperor was grateful for the part Wolsey had played in his secure arrival and must have thought sailing back to Spain from the Netherlands, if matters were arranged and managed with the same efficiency as the outward journey, would be a breeze.

Back to War

However, soon after Charles was crowned, the peace with France that had held since 1518 was shattered. By the spring of 1521, fighting had broken out in both Luxemburg and Navarre. Each side blamed the other. Accusations flew on one side that the Valois dynasty had started it and on the other side that the Habsburg dynasty had started it; it was even rumoured that some third party had started it. For Charles, who needed to get back to Spain, this was a dangerous situation.

For Wolsey, the arch negotiator, the resulting situation could not have been more convenient if he had engineered it himself. Charles was stuck in the Netherlands when he soon needed to be in Spain but he would be in mortal danger if he left by either land or sea.

Calais, Bruges and Double-Dealing

Wolsey was soon in action: he pulled on his arbiter’s hat, marshalled his great entourage, which included Thomas Ruthall, Cuthbert Tunstall and Thomas More, and set off across the Channel, arriving at Calais on 2 August 1522. The fighting continued unabated, and ostensibly he was there to direct a peace conference. The first session was held on 7 August, and the Habsburg and Valois representatives were present. Charles waited on safe territory in Bruges, from where he wrote to Wolsey and asked the cardinal to go and meet him there.

In response, Wolsey, supposedly the impartial mediator, bluffed the French and went off to meet the emperor in Bruges, where they negotiated a treaty to their own advantage but excluding and to the detriment of the French. The treaty contracted Charles to a future marriage with Henry’s daughter Princess Mary; she was five at the time and of course the marriage never happened.

Beyond all the marriage stipulations, however, most of the remainder of the treaty dealt with Charles’s return to Spain the following spring and the protection he would receive on the journey from the English navy. The return was to be coordinated with a joint, simultaneous declaration of war against France. Wolsey agreed to all this and in return Charles promised to make him pope.

Death of a Pope

It was 29 August before the cardinal arrived back in Calais, and he and his diplomats, one of whom was Thomas Boleyn, had to choreograph some deft diplomatic moves to persuade the French delegation that there had been no double-dealing in Bruges. Indeed the peace talks continued on until November 1521, and Wolsey’s main purpose from that point on was to fool the French into believing England was friendly and neutral.

Wolsey, with his pledge from Charles that he would be the next pope, sailed back to England on 28 November 1521.

Then, three days later on, 1 December, Pope Leo X was dead.

It was 29 August before the cardinal arrived back in Calais, and he and his diplomats, one of whom was Thomas Boleyn, had to choreograph some deft diplomatic moves to persuade the French delegation that there had been no double-dealing in Bruges. Indeed the peace talks continued on until November 1521, and Wolsey’s main purpose from that point on was to fool the French into believing England was friendly and neutral.

Wolsey, with his pledge from Charles that he would be the next pope, sailed back to England on 28 November 1521.

Then, three days later on, 1 December, Pope Leo X was dead.