|

A Recap

Previously, in part one, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, the Papa of Christendom, while playing the part of arbiter between King Francis I of France and Charles Holy Roman Emperor, far from being an honest, and neutral broker had entered into a secret pact, the Treaty of Bruges, with Charles, Holy Roman Emperor, King of Spain to ally against France.

The treaty demanded that the English Navy protect Charles from the threat of French warships in the English Channel and so allow him to return in safety from the Low Countries to Spain.

It was also agreed, in part 3 of the treaty;

3. The contracting parties to declare themselves open enemies to the king of France in March 1523, and make war upon him by land and sea, viz., the Pope and Emperor together in Italy, for the expulsion of the French before the 15th of May in that year, the Pope using the spiritual arm only, but the Emperor furnishing 10,000 horse and 30,000 foot.

Pope Leo X

All this while Wolsey was supposed to be brokering a peace deal!

In return, Charles, ostensibly recognising Wolsey’s abilities, had given an undertaking that he would support the cardinal in his insatiable ambition to be pope when Pope Leo X died.

The deal done, Wolsey returned home. Three days later Pope Leo dropped dead. He died so suddenly that there was no time even for the last sacraments.

With Leo dead, Wolsey was duly entered as a candidate for the consequent papal election.

Previously, in part one, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, the Papa of Christendom, while playing the part of arbiter between King Francis I of France and Charles Holy Roman Emperor, far from being an honest, and neutral broker had entered into a secret pact, the Treaty of Bruges, with Charles, Holy Roman Emperor, King of Spain to ally against France.

The treaty demanded that the English Navy protect Charles from the threat of French warships in the English Channel and so allow him to return in safety from the Low Countries to Spain.

It was also agreed, in part 3 of the treaty;

3. The contracting parties to declare themselves open enemies to the king of France in March 1523, and make war upon him by land and sea, viz., the Pope and Emperor together in Italy, for the expulsion of the French before the 15th of May in that year, the Pope using the spiritual arm only, but the Emperor furnishing 10,000 horse and 30,000 foot.

Pope Leo X

All this while Wolsey was supposed to be brokering a peace deal!

In return, Charles, ostensibly recognising Wolsey’s abilities, had given an undertaking that he would support the cardinal in his insatiable ambition to be pope when Pope Leo X died.

The deal done, Wolsey returned home. Three days later Pope Leo dropped dead. He died so suddenly that there was no time even for the last sacraments.

With Leo dead, Wolsey was duly entered as a candidate for the consequent papal election.

Charles Old School Teacher - Pope Adrian

Charles Old School Teacher - Pope Adrian

A New Pope – Not Wolsey but Charles’ Old School Teacher

The sudden turn of events caught Charles by surprise but conveniently for him, when the election was held rival Italian factions caused chaos in Rome. The infighting allowed Charles to slip Adrian, his regent in Spain into the papal office as Pope Adrian VI. Adrian had been Charles’ childhood tutor in the Low Countries, and with that appointment, the emperor stalled Wolsey with a bluff to the effect that Adrian was a subordinate stopgap to keep the tall hat warm until he got back to Spain. Charles would sort things out, in Wolsey’s favour, when things settled down. Charles in the meantime Charles instructed Adrian to appoint Wolsey as Abbott of St Albans, one of the richest monasteries in England.

Adrian, therefore, was the pope but, for now, a pope who lived in Spain. Maybe that was where Charles intended him to stay (Adrian made for Rome before Charles got back and turned out to be something of a renegade) and so move the papal office to Toledo - maybe.

Spain Lauds the English Armáda

The spring of 1522 arrived and, having reappointed Margaret as regent, Charles departed from Brussels for Spain, via England on 23 May. The arrangements agreed in the Bruges Treaty to get him there safely were put into operation.

Henry VIII’s herald was dispatched across the Channel to declare war on France. Charles arrived at Calais on 26 May and crossed to Dover the next day, escorted by the English fleet with a complement of over 10,000 men.

King Francis was handed the war declaration at Lyon on 29 May.

On 6 June, Charles and Henry travelled from Greenwich to London, cheered along the way by excited crowds. A few days later, amid much pomp and ceremony, they went on to Windsor and held talks about Wolsey’s papal aspirations. From there they continued towards Southampton. (a change of plan, the treaty had designated Falmouth as the port of departure).

The sudden turn of events caught Charles by surprise but conveniently for him, when the election was held rival Italian factions caused chaos in Rome. The infighting allowed Charles to slip Adrian, his regent in Spain into the papal office as Pope Adrian VI. Adrian had been Charles’ childhood tutor in the Low Countries, and with that appointment, the emperor stalled Wolsey with a bluff to the effect that Adrian was a subordinate stopgap to keep the tall hat warm until he got back to Spain. Charles would sort things out, in Wolsey’s favour, when things settled down. Charles in the meantime Charles instructed Adrian to appoint Wolsey as Abbott of St Albans, one of the richest monasteries in England.

Adrian, therefore, was the pope but, for now, a pope who lived in Spain. Maybe that was where Charles intended him to stay (Adrian made for Rome before Charles got back and turned out to be something of a renegade) and so move the papal office to Toledo - maybe.

Spain Lauds the English Armáda

The spring of 1522 arrived and, having reappointed Margaret as regent, Charles departed from Brussels for Spain, via England on 23 May. The arrangements agreed in the Bruges Treaty to get him there safely were put into operation.

Henry VIII’s herald was dispatched across the Channel to declare war on France. Charles arrived at Calais on 26 May and crossed to Dover the next day, escorted by the English fleet with a complement of over 10,000 men.

King Francis was handed the war declaration at Lyon on 29 May.

On 6 June, Charles and Henry travelled from Greenwich to London, cheered along the way by excited crowds. A few days later, amid much pomp and ceremony, they went on to Windsor and held talks about Wolsey’s papal aspirations. From there they continued towards Southampton. (a change of plan, the treaty had designated Falmouth as the port of departure).

Mary Rose Commissioned to Head the Spanish Fleet

The Mary Rose was moored at Southampton and Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey, was aboard. Howard had been appointed Admiral of the Fleet, that is to say, he was in command of both the English and the Spanish navies, which were tasked with returning Charles to Spain unharmed.

At the end of June, Howard sailed west from Southampton and waited at Dartmouth. From Dartmouth, he sailed across the Channel clearing the way for Charles to return home.

He sacked the French port of Morlaix. Then on westward to Saint-Pol-de-Léon and burned it down then to the most westerly port in France, Le Conquet, and bombarded that too.

On 7 July Charles left England from Southampton for Spain. Howard, the Mary Rose and the English Navy had made the way safe for him.

The Mary Rose was moored at Southampton and Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey, was aboard. Howard had been appointed Admiral of the Fleet, that is to say, he was in command of both the English and the Spanish navies, which were tasked with returning Charles to Spain unharmed.

At the end of June, Howard sailed west from Southampton and waited at Dartmouth. From Dartmouth, he sailed across the Channel clearing the way for Charles to return home.

He sacked the French port of Morlaix. Then on westward to Saint-Pol-de-Léon and burned it down then to the most westerly port in France, Le Conquet, and bombarded that too.

On 7 July Charles left England from Southampton for Spain. Howard, the Mary Rose and the English Navy had made the way safe for him.

Brandon's Invasion and Charles’s Broken Pledge

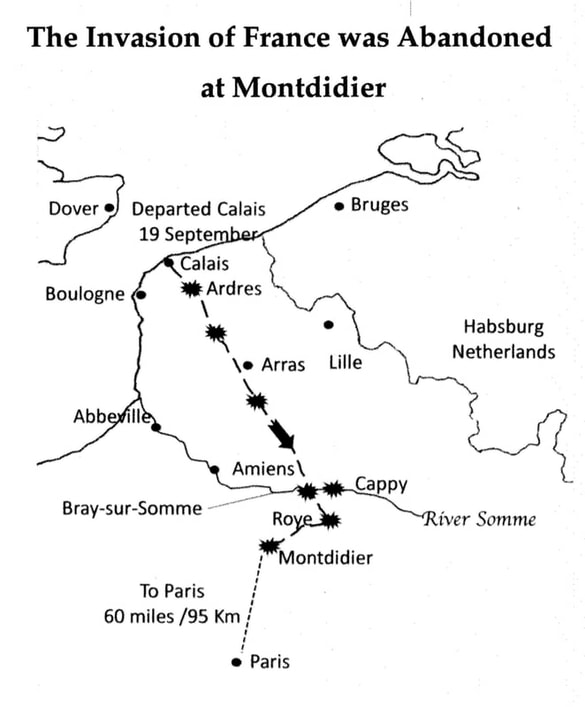

The invasion of France began in early autumn 1523, and the Duke of Suffolk, Charles Brandon moved off south, from Calais with his troops on 19 September.

Low and behold, within a few days of the invasion, news arrived. Pope Adrian had dropped dead, on 14 September. The timing of this for Wolsey couldn’t have been more spectacular if he had arranged it himself. Now his time for the papacy had come - surely?

The cardinal was entered for election and waited for the result.

Meanwhile, honouring the Bruges Treaty Brandon pushed on into France and made impressive progress south towards Paris. Wolsey had expected to hear quickly. He expected his election to be a formality and exchanged correspondence about it with his agents in Rome, Pace and Hannibal.

Then he became pensive: Time went on, and there were letters from Rome but still no news about the election.

Then it did come: the news. Wolsey had lost. The Medici family had recovered the papacy, and Giulio di Giuliano de' Medici would become Clement VII

In France, Charles Brandon had made such spectacular progress that he was just waiting for a supply of battering rams to arrive so that he could knock down the walls of Paris. The city was there for the taking, but the supply line from England was becoming a problem.

In England Wolsey was devastated. That was it for him and the Habsburgs. They had used him; they had used the protection of ‘his’ navy and had used him to secure the Netherlands, and he had got nothing out of it at all.

Brandon was at Montdidier and suddenly overburdened with problems. The pay for his troops had not arrived, neither had the reinforcements he had called for, and there was no sign of his battering rams for the walls of Paris. The 1523 campaign to conquer France collapsed, the dissembling Wolsey had pulled the plug. Bewildered, Brandon was forced into a rapid retreat.

Wolsey had decided his aspirations were better served away from the Habsburgs. The de facto ruler of England resolved to ally himself with the French Valois dynasty and began talks, secretly from Henry with French agents, and in August the following year signed the Treaty of the More, an alliance between England and France.

The invasion of France began in early autumn 1523, and the Duke of Suffolk, Charles Brandon moved off south, from Calais with his troops on 19 September.

Low and behold, within a few days of the invasion, news arrived. Pope Adrian had dropped dead, on 14 September. The timing of this for Wolsey couldn’t have been more spectacular if he had arranged it himself. Now his time for the papacy had come - surely?

The cardinal was entered for election and waited for the result.

Meanwhile, honouring the Bruges Treaty Brandon pushed on into France and made impressive progress south towards Paris. Wolsey had expected to hear quickly. He expected his election to be a formality and exchanged correspondence about it with his agents in Rome, Pace and Hannibal.

Then he became pensive: Time went on, and there were letters from Rome but still no news about the election.

Then it did come: the news. Wolsey had lost. The Medici family had recovered the papacy, and Giulio di Giuliano de' Medici would become Clement VII

In France, Charles Brandon had made such spectacular progress that he was just waiting for a supply of battering rams to arrive so that he could knock down the walls of Paris. The city was there for the taking, but the supply line from England was becoming a problem.

In England Wolsey was devastated. That was it for him and the Habsburgs. They had used him; they had used the protection of ‘his’ navy and had used him to secure the Netherlands, and he had got nothing out of it at all.

Brandon was at Montdidier and suddenly overburdened with problems. The pay for his troops had not arrived, neither had the reinforcements he had called for, and there was no sign of his battering rams for the walls of Paris. The 1523 campaign to conquer France collapsed, the dissembling Wolsey had pulled the plug. Bewildered, Brandon was forced into a rapid retreat.

Wolsey had decided his aspirations were better served away from the Habsburgs. The de facto ruler of England resolved to ally himself with the French Valois dynasty and began talks, secretly from Henry with French agents, and in August the following year signed the Treaty of the More, an alliance between England and France.

No Forgiveness for this Enemy

Wolsey never forgave Charles. The union between England and the empire and between the Tudors and the Habsburgs had been secured with the marriage of Henry VIII to Catherine of Aragon. So far as Wolsey was concerned, this union, both the marriage and the political alliance, had to go; it was unsustainable - Henry VIII must divorce Catherine of Aragon.

In the years that followed Catherine hated Wolsey for what he did to her, her nephew and her marriage, and she showed it as the cardinal tried to dissolve the union. In 1529 she said this;

Wolsey never forgave Charles. The union between England and the empire and between the Tudors and the Habsburgs had been secured with the marriage of Henry VIII to Catherine of Aragon. So far as Wolsey was concerned, this union, both the marriage and the political alliance, had to go; it was unsustainable - Henry VIII must divorce Catherine of Aragon.

In the years that followed Catherine hated Wolsey for what he did to her, her nephew and her marriage, and she showed it as the cardinal tried to dissolve the union. In 1529 she said this;

“But of this I only may thank you my Lord Cardinal of York, for because I have wondered at your high pride and vainglory, and abhor your voluptuous [pleasures of the body/gratification] life and abominable, lechery and little regard your presupeous [presumptuous] power and tyranny.

Therefore of malice you have kindled this fire and set this matter a broche, in especial for the great malice, that you bear to my nephew the Emperor, whom I perfectly know you hate worse than a scorpion because he would not satisfy your ambition and make you Pope by force.

And therefore you have said more than once that you would trouble him and his friends and you have kept him a true promise for all his warres and vexations he may only thank you, and as for me his poor aunte and kinswoman what trouble you put me to by this new found doubt.

God knows to whom I commit my cause according to the truth.”

In 1523 Clement VII was made pope. Cardinal Wolsey had lost again. He blamed Charles and so it was then that the destruction, orchestrated by the cardinal, of the matrimonial union between Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon began

M.H.