Henry VIII, the Reign

Collectanea satis copiosa and A Green and Pleasant Land

Thomas Cromwell

Thomas Cromwell

The preamble to the Act of Parliament, the Act of Appeals that severed England from papal authority began with the following statement which expressed the purpose and underlying philosophy of the new law.

‘Where by divers sundry old authentic histories and chronicles it is manifestly declared and expressed that this realm of England is an empire, and so hath been accepted in the world, governed by one supreme head and king having the dignity and royal estate of the imperial crown of the same…’

The law affirmed that England was an empire, the realm had one supreme head, always had done and the authentic histories and chronicles proved it so.

But how authentic were these histories that have shaped history ever since?

To some they are but the work of the twelfth century Welsh fantasist, Geoffrey of Monmouth and associated with more modern day Walt Disney and Monty Python productions.

The stuff of old wives tales and fable...or were they?

‘Where by divers sundry old authentic histories and chronicles it is manifestly declared and expressed that this realm of England is an empire, and so hath been accepted in the world, governed by one supreme head and king having the dignity and royal estate of the imperial crown of the same…’

The law affirmed that England was an empire, the realm had one supreme head, always had done and the authentic histories and chronicles proved it so.

But how authentic were these histories that have shaped history ever since?

To some they are but the work of the twelfth century Welsh fantasist, Geoffrey of Monmouth and associated with more modern day Walt Disney and Monty Python productions.

The stuff of old wives tales and fable...or were they?

Collapse of the Blackfriars Trial and Thomas Wolsey

Campeggio

Campeggio

The Collectanea satis copiosa translated into English reads the Sufficiently Abundant Collections. It is a compilation of historical documents, a copy of which is held in the British Library, and it is purported to demonstrate that kings and queens of England had no superiors in the world, including the pope.

The Act of Parliament that severed England’s subservience to papal authority was the Ecclesiastical Appeals Act 1532, also called the Statute in Restraint of Appeals and the Act of Appeals. The Act prevented all appeals to the pope in Rome on religious or indeed any other matters, and this made the monarch the highest legal authority in England.

In 1529, the Blackfriars trial of the validity of Henry VIII’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon collapsed in chaos. Initially, the two cardinals, Wolsey and Campeggio, who were running the proceedings, shocked everyone by deferring judgement and declaring an unexpected, immediate summer recess. Hot on the heels of that shock came news that, as a consequence of the recent change in the political balance of Christendom, Pope Clement had called for the case to be transferred from London to Rome, where it was to be decided.

Henry walked out of the proceedings and left his brother-in-law, Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, to berate the two cardinals.

The Act of Parliament that severed England’s subservience to papal authority was the Ecclesiastical Appeals Act 1532, also called the Statute in Restraint of Appeals and the Act of Appeals. The Act prevented all appeals to the pope in Rome on religious or indeed any other matters, and this made the monarch the highest legal authority in England.

In 1529, the Blackfriars trial of the validity of Henry VIII’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon collapsed in chaos. Initially, the two cardinals, Wolsey and Campeggio, who were running the proceedings, shocked everyone by deferring judgement and declaring an unexpected, immediate summer recess. Hot on the heels of that shock came news that, as a consequence of the recent change in the political balance of Christendom, Pope Clement had called for the case to be transferred from London to Rome, where it was to be decided.

Henry walked out of the proceedings and left his brother-in-law, Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, to berate the two cardinals.

Waltham Holy Cross and Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer

Henry, however, had wiser adherents about him, and the Boleyns soon had the contingency plan wheeled out and set in motion; unfortunately for Wolsey, it ran him over.

Henry had delayed his summer progress and stayed close to Blackfriars for the trial. From 8 July he had been at Bridewell, and from 15 July at Durham House, the London residence of the Boleyns, but after the collapse of the proceedings he set off for Waltham in Essex via Greenwich, arriving there on 2 August.

In the royal entourage were Edward Fox, future Bishop of Worcester, and Stephen Gardiner, future Bishop of Winchester. Both had been involved in the toing and froing between Rome and Orvieto while the pope was a prisoner there.

Waltham had been chosen purposefully to further the cause of the divorce. Since about 1035 Waltham had been the home of the legendary Holy Cross brought there by the Dane, Tovi the Proud. Here was a place for the discovery of ‘divers sundry old authentic histories and chronicles’. Here would be laid foundation of the case against Rome and the annulment of the marriage between Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon. To help them make their case, Fox and Gardiner brought in Thomas Cranmer, a friend from their Cambridge days, who would soon be the Archbishop of Canterbury. In Waltham, they discussed involving various universities throughout Christendom to support the religious arguments; however, the principle idea, prompted by the Boleyns, endorsed by Cranmer, was to attack the problem from the roots up, remove the pope and papal influence from the equation altogether, and thus rid England of his jurisdiction.

Henry had delayed his summer progress and stayed close to Blackfriars for the trial. From 8 July he had been at Bridewell, and from 15 July at Durham House, the London residence of the Boleyns, but after the collapse of the proceedings he set off for Waltham in Essex via Greenwich, arriving there on 2 August.

In the royal entourage were Edward Fox, future Bishop of Worcester, and Stephen Gardiner, future Bishop of Winchester. Both had been involved in the toing and froing between Rome and Orvieto while the pope was a prisoner there.

Waltham had been chosen purposefully to further the cause of the divorce. Since about 1035 Waltham had been the home of the legendary Holy Cross brought there by the Dane, Tovi the Proud. Here was a place for the discovery of ‘divers sundry old authentic histories and chronicles’. Here would be laid foundation of the case against Rome and the annulment of the marriage between Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon. To help them make their case, Fox and Gardiner brought in Thomas Cranmer, a friend from their Cambridge days, who would soon be the Archbishop of Canterbury. In Waltham, they discussed involving various universities throughout Christendom to support the religious arguments; however, the principle idea, prompted by the Boleyns, endorsed by Cranmer, was to attack the problem from the roots up, remove the pope and papal influence from the equation altogether, and thus rid England of his jurisdiction.

Joseph of Arimathea

The three men developed the theory that Christianity had been brought to the British Isles in the lifetime of Christ or immediately after his death by Joseph of Arimathea, that the very first Christian church in the world had been built at Glastonbury and that only after the Roman Emperor Constantine’s father had died, almost four hundred years later, in York, had the Christian religion been exported from England to Rome.

Their premise was that if British Christianity predated Roman Christianity and if it had been firmly established in the isles before the arrival of Augustine from Rome some six hundred years later, then the ultimate ruling authority of the church must be an inherent part of the reigning monarch’s powers and not part of the powers of the Bishop of Rome, who in the interim period usurped it. They prepared to put the idea to the king while he remained lodged at Waltham and so polished their account of the story of Tovi and Waltham’s Holy Cross.

Their premise was that if British Christianity predated Roman Christianity and if it had been firmly established in the isles before the arrival of Augustine from Rome some six hundred years later, then the ultimate ruling authority of the church must be an inherent part of the reigning monarch’s powers and not part of the powers of the Bishop of Rome, who in the interim period usurped it. They prepared to put the idea to the king while he remained lodged at Waltham and so polished their account of the story of Tovi and Waltham’s Holy Cross.

|

Above "Pontius Pilate has granted Joseph of Arimathea permission to take Christ's body down from the cross for burial. He is aided by Saint John, who is holding Christ's hand, and by Nicodemus, with his back to us..."

|

Tovi the Proud

In Waltham, Tovi the Dane once held large estates in Essex and Somerset, one of which, in Somerset, was at Montacute, near Glastonbury. In 1035, a buried flint cross was discovered. It was believed to be part of the True Cross on which Jesus died and which was brought to Montacute by Joseph of Arimathea.

Tovi arranged to have the cross moved. It was loaded on to a cart to be pulled by a dozen oxen, six red and six white; it was no small cross, and the oxen were uncertain where to take it. Tovi demanded the beasts pull it to a holy place but they would not move until he said, ‘Waltham,’ and only then did they move off, immediately, towards Waltham. Maybe they were merely responding to what they heard as ‘Walk on’, but that rather deflates the legend’s mysticism; nonetheless, they apparently did not stop until they reached Waltham, where the cross was erected and the great Abbey of Waltham was built around Joseph of Arimathea’s Holy Cross.

Fox and Gardiner presented the idea to Henry that the king of England, not the pope, should be head of the church in England, and he liked it. Soon Thomas Cranmer was working on developing it further in London, with the Boleyns at Durham Place. With Fox assisting closely, they compiled a host of other writings to support their assertions. Cranmer was now a busy man; he canvassed a number of universities in England and on the Continent, but was back in time to review the collection before it was presented in book form to Henry VIII. Henry VII had claimed that he had traced his ancestry back to King Arthur and so named his eldest son Arthur, and thus Arthurian fables were added to the collection together with works by Bede, Matthew Paris, William of Malmesbury and Geoffrey of Monmouth.

Henry was delighted with the finished article; the annotations in his own hand are preserved to this day in the copy at the British Library.

But is this all the stuff of Disney and Monty Python dreamt up by fantasist monks in medieval times?

Tovi arranged to have the cross moved. It was loaded on to a cart to be pulled by a dozen oxen, six red and six white; it was no small cross, and the oxen were uncertain where to take it. Tovi demanded the beasts pull it to a holy place but they would not move until he said, ‘Waltham,’ and only then did they move off, immediately, towards Waltham. Maybe they were merely responding to what they heard as ‘Walk on’, but that rather deflates the legend’s mysticism; nonetheless, they apparently did not stop until they reached Waltham, where the cross was erected and the great Abbey of Waltham was built around Joseph of Arimathea’s Holy Cross.

Fox and Gardiner presented the idea to Henry that the king of England, not the pope, should be head of the church in England, and he liked it. Soon Thomas Cranmer was working on developing it further in London, with the Boleyns at Durham Place. With Fox assisting closely, they compiled a host of other writings to support their assertions. Cranmer was now a busy man; he canvassed a number of universities in England and on the Continent, but was back in time to review the collection before it was presented in book form to Henry VIII. Henry VII had claimed that he had traced his ancestry back to King Arthur and so named his eldest son Arthur, and thus Arthurian fables were added to the collection together with works by Bede, Matthew Paris, William of Malmesbury and Geoffrey of Monmouth.

Henry was delighted with the finished article; the annotations in his own hand are preserved to this day in the copy at the British Library.

But is this all the stuff of Disney and Monty Python dreamt up by fantasist monks in medieval times?

Last Night of The Proms, Tin and Bronze

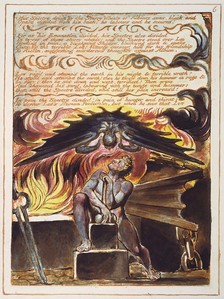

Blake's Jerusalem Plate 6

Blake's Jerusalem Plate 6

William Blake asked questions in his poem ‘And did those feet in ancient time’, famously known as the anthem Jerusalem, with music written by Sir Hubert Parry; it is now traditionally sung on the last night of the Promenade Concerts at the Royal Albert Hall in London. Blake alludes to Jesus himself coming to England.

Blake’s questions still remained unanswered at the time when Van Morrison wrote Summertime in England, and the coming will always remain legendary; however, it is plausible that Jesus, Joseph of Arimathea and St Paul the apostle did come to England.

The Roman Empire, at that time yet to conquer England and Wales, demanded vast amounts of tin for making bronze, not least in the eastern Mediterranean, the home of Jesus, Joseph and St Paul. The principle sources for tin, apart from the landlocked Ore Mountains in Germany, were north-west Spain, Brittany in north-west France and Devon and Cornwall in England; all of these areas were once the home of Gaelic communities.

St Paul spent time in Spain, and Clement of Rome wrote that ‘Paul was herald of the gospel in the West,’ and that ‘he had gone to the extremity of the west’. Paul wrote his Epistle to the Galatians, usually shortened to Galatians, which of course is the ninth book of the New Testament.

Perhaps one man’s gospel is mere legend to another and the stuff of Disney and Monty Python to another, but whatever the interpretation, the consequence of it all is encapsulated in the preamble – the introduction – to the Statute in Restraint of Appeals, which states:

Where by divers sundry old authentic histories and chronicles it is manifestly declared and expressed that this realm of England is an empire, and so hath been accepted in the world, governed by one supreme head and king having the dignity and royal estate of the imperial crown of the same, unto whom a body politic, compact of all sorts and degrees of people divided in terms and by names of spirituality and temporality, be bounden and owe to bear next to God a natural and humble obedience; he being also institute and furnished by the goodness and sufferance of Almighty God with plenary, whole and entire power, pre-eminence, authority, prerogative and jurisdiction to render and yield justice and final determination to all manner of folk resiants or subjects within this realm, in all causes, manners, debates and contentions happening to occur…

Having exercised his power as the one supreme head of the church, Henry VIII was divorced from Catherine of Aragon and married in her stead Ann Boleyn.

Blake’s questions still remained unanswered at the time when Van Morrison wrote Summertime in England, and the coming will always remain legendary; however, it is plausible that Jesus, Joseph of Arimathea and St Paul the apostle did come to England.

The Roman Empire, at that time yet to conquer England and Wales, demanded vast amounts of tin for making bronze, not least in the eastern Mediterranean, the home of Jesus, Joseph and St Paul. The principle sources for tin, apart from the landlocked Ore Mountains in Germany, were north-west Spain, Brittany in north-west France and Devon and Cornwall in England; all of these areas were once the home of Gaelic communities.

St Paul spent time in Spain, and Clement of Rome wrote that ‘Paul was herald of the gospel in the West,’ and that ‘he had gone to the extremity of the west’. Paul wrote his Epistle to the Galatians, usually shortened to Galatians, which of course is the ninth book of the New Testament.

Perhaps one man’s gospel is mere legend to another and the stuff of Disney and Monty Python to another, but whatever the interpretation, the consequence of it all is encapsulated in the preamble – the introduction – to the Statute in Restraint of Appeals, which states:

Where by divers sundry old authentic histories and chronicles it is manifestly declared and expressed that this realm of England is an empire, and so hath been accepted in the world, governed by one supreme head and king having the dignity and royal estate of the imperial crown of the same, unto whom a body politic, compact of all sorts and degrees of people divided in terms and by names of spirituality and temporality, be bounden and owe to bear next to God a natural and humble obedience; he being also institute and furnished by the goodness and sufferance of Almighty God with plenary, whole and entire power, pre-eminence, authority, prerogative and jurisdiction to render and yield justice and final determination to all manner of folk resiants or subjects within this realm, in all causes, manners, debates and contentions happening to occur…

Having exercised his power as the one supreme head of the church, Henry VIII was divorced from Catherine of Aragon and married in her stead Ann Boleyn.

Last Abbey to be Closed

It finished where it started.

Of all the scores of monasteries closed in the reign of Henry VIII, Waltham Abbey was the last to be dissolved, on 23 March 1540.

Of all the scores of monasteries closed in the reign of Henry VIII, Waltham Abbey was the last to be dissolved, on 23 March 1540.