Charles V of Spain sailed in peacetime from Santander to be crowned Holy Roman Emperor in Archem Germany.

While he was there hostilities broke out in both northern and southern Europe which had the effect of placing Charles in mortal danger for the return voyage to Spain in 1522.

The Mary Rose, one of the most famous English warships ever built, was instrumental in returning the Spanish king home safely.

However, the exploits of English naval prowess in support of Spain during the summer of 1522 led to the English repudiation of the Habsburgs and the eventual split from Rome.

Charles V, the King of Spain, was elected Holy Roman Emperor in 1519 by a unanimous vote, defeating his principle rival Francis I, the King of France. The effect of his election was to unite the territories Charles had inherited from his maternal grandfather, Ferdinand, with those of his paternal grandfather, Maximilian, in the name of Habsburg. For the rest of their lives, Valois Francis and Habsburg Charles would be bitter enemies.

The ceremony for the coronation of the Holy Roman Emperor, established over many centuries, was a series of rituals, the first of which took place in Aachen, in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. This presented some difficulties for Charles because at the time of his election he lived in Spain.

The English Channel and the Imperial Crown

There was peace in Europe in 1519 because the Treaty of London, organised in 1518 by Thomas Wolsey, Cardinal Archbishop of York and Papal Legate, had been upheld. Any peace, however, between the Habsburg and Valois dynasties was fragile and was likely to be broken at any moment. Francis held military sway in northern Italy but Charles needed to establish communications between his vast territories now united under one sceptre in Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain. There were two alternative routes, either through the Strait of Dover to the port of Flushing (Vlissingen) in the Netherlands or from Barcelona to Genoa and then through Millan to the Tyrol. Innsbruck to Aachen, however, was still another 450 miles overland, and by going that way he would always be vulnerable to attack from France, and in the Mediterranean he would also be threatened by the Turks.

Any French threat in the Strait of Dover, however, could be parried by the alliance with England, which was sealed by his aunt Catherine of Aragon’s marriage to Henry VIII. England possessed a powerful navy, and Uncle Henry would be flattered to be the first monarch to receive the Holy Roman Emperor elect as a guest. The original plan was for Charles to disembark at Southampton and travel overland, meeting up again with his ships at Dover, re-embarking there and so avoiding the Strait of Dover altogether.

Cardinal Wolsey placed himself in charge of the arrangements on the English side.

Wolsey's Seasaw

For the time being, England was pivotal in the balance of power between Valois France on the one side and the expanding Habsburg Empire on the other. The infinitely ambitious Wolsey had by this time appointed himself as a sort of steward of Christendom, the wise man presiding over the three inexperienced young monarchs, Charles, aged nineteen, Francis, twenty-four and Henry, twenty-eight.

Wolsey’s career with Henry VIII had begun with him as the youthful king’s almoner; he was then promoted to be Bishop of Lincoln, and after that very quickly became the Archbishop of York, then Cardinal Archbishop and then the Papal Legate in England. Now he was after the top job, the papacy itself.

Charles set sail from La Carruna and left Adrian of Utrecht, his former tutor and adviser in the Netherlands, with the daunting task of administering the kingdom of Spain as regent during his absence. Adrian had been a senior administrator in Spain since 1515.

Wolsey, as Charles sailed north, was erring towards the French and King Francis for support in relation to his aspirations to become pope. In return, he pledged England’s political and military assistance to France with the intention of tipping the balance of power in favour of the Valois dynasty over the Hapsburgs, but Wolsey was always open to an improved arrangement.

The Field of the Cloth of Gold

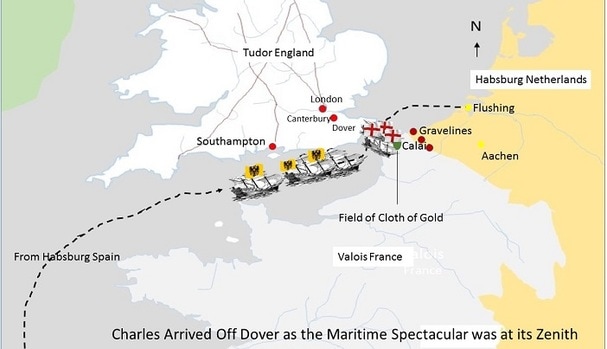

The French king and Henry VIII had often expressed a desire to meet each other and so Wolsey arranged an outlandishly lavish event that became known as the Field of the Cloth of Gold, infamous for its glamour, extravagance and apparent lack of political significance.

Francis, at some point during it all, beat Henry at wrestling, which is perhaps worthy of note.

Anyway, the staging of such an event was a logistical marvel in its day and would still be a remarkable achievement today. The total number of Henry’s company for the revels was estimated at 4,000 people and over 2,000 horses and Queen Catherine’s at over 1,000 people and more than 750 horses. There were dukes and earls, bishops, barons and a marquis, together with an army of priests. Then there were tents, timber for buildings, costumes for revels, the king’s bed, all the paraphernalia for the jousting, marvellous statues of ancient princes, probably a kitchen sink or two, and so on and so on. All this was shipped across to France by the splendid power of the English navy.

A Maritime Spectacular

Charles made good time from Spain and, rather than land at Southampton, Wolsey rowed out to meet him, and for his trouble Charles granted him the financial rewards of an entire Spanish bishopric and the substantial part of the revenues of another.

On Whit Sunday, 27 May 1520, Charles rode at the head of a procession from Dover to Canterbury, where the great royal meeting took place and Henry VIII and Queen Catherine embraced their nephew for the first time. Over the next few days, some treaties were signed and then Charles rode back to Dover and sailed on to Flushing while Henry and Wolsey headed to Calais and then on to the jolly in the field.

After the Field of Cloth of Gold, Henry and Wolsey met Charles again at Gravelines, a few miles north of Calais.

All had gone safely for Charles, and he was crowned with the Iron Crown of Lombardy in the great cathedral of Charlemagne in Aachen on 23 July 1520.The emperor was grateful for the part Wolsey had played in his secure arrival and must have thought sailing back to Spain from the Netherlands, if matters were arranged and managed with the same efficiency as the outward journey, would be a breeze.

Back to War

However, soon after Charles was crowned, the peace with France that had held since 1518 was shattered. By the spring of 1521, fighting had broken out in both Luxemburg and Navarre. Each side blamed the other. Accusations flew on one side that the Valois dynasty had started it and on the other side that the Habsburg dynasty had started it; it was even rumoured that some third party had started it. For Charles, who needed to get back to Spain, this was a dangerous situation.

For Wolsey, the arch negotiator, the resulting situation could not have been more convenient if he had engineered it himself. Charles was stuck in the Netherlands when he soon needed to be in Spain but he would be in mortal danger if he left by either land or sea.

Calais, Bruges and Double-Dealing

Wolsey was soon in action: he pulled on his arbiter’s hat, marshalled his great entourage, which included Thomas Ruthall, Cuthbert Tunstall and Thomas More, and set off across the Channel, arriving at Calais on 2 August 1522. The fighting continued unabated, and ostensibly he was there to direct a peace conference. The first session was held on 7 August, and the Habsburg and Valois representatives were present. Charles waited on safe territory in Bruges, from where he wrote to Wolsey and asked the cardinal to go and meet him there.

In response, Wolsey, supposedly the impartial mediator, bluffed the French and went off to meet the emperor in Bruges, where they negotiated a treaty to their own advantage but excluding and to the detriment of the French. The treaty contracted Charles to a future marriage with Henry’s daughter Princess Mary; she was five at the time and of course the marriage never happened.

Beyond all the marriage stipulations, however, most of the remainder of the treaty dealt with Charles’s return to Spain the following spring and the protection he would receive on the journey from the English navy. The return was to be coordinated with a joint, simultaneous declaration of war against France. Wolsey agreed to all this and in return Charles promised to make him pope.

Death of a Pope, Charles on the Hop

It was 29 August before the cardinal arrived back in Calais, and he and his diplomats, one of whom was Thomas Boleyn, had to choreograph some deft diplomatic moves to persuade the French delegation that there had been no double-dealing in Bruges. Indeed the peace talks continued on until November 1521, and Wolsey’s main purpose from that point on was to fool the French into believing England was friendly and neutral.

Wolsey, with his pledge from Charles that he would be the next pope, sailed back to England on 28 November 1521.

Pope Leo X died on 1 December.

He died so suddenly that there was no time to administer the last sacraments. The timing of his death could not have been more spectacular if Wolsey had contrived it himself. Wolsey was entered as a candidate for the subsequent papal election.

The sudden turn of events caught Charles on the hop, however; conveniently for him, when the election was held rival Italian factions caused chaos in Rome. The infighting allowed Charles to slip Adrian, his regent in Spain, into the papal office as Pope Adrian VI. With that appointment, the emperor could stall Wolsey, bluff him with a story as a sop about Adrian being a subordinate stopgap to keep the throne warm until he got back to Spain and could sort things out in Wolsey’s favour. He also told Adrian to appoint Wolsey as Abbott of St Albans, which was one of the richest monasteries in England.

Spain Lauds the English Armáda

Adrian, therefore, was the pope but, for now, a pope who was resident in Spain. Perhaps that was where Charles intended him to stay.

The spring of 1522 arrived and, having reappointed Margaret as regent, Charles departed from Brussels for Spain on 23 May. The Bruges plan to get him there safely was put into operation. Henry VIII’s herald was despatched to France to declare war on the duped French. Charles arrived at Calais on 26 May and crossed to Dover the next day escorted by the English fleet with a complement of over 10,000 men.

Francis was handed the war declaration in Lyon on 29 May. It seems he was not completely surprised – perhaps Wolsey’s bluffing had not been so convincing.

On 6 June, Charles and Henry went from Greenwich to London, surrounded along the way by cheering crowds. Amid all the pomp and ceremony, a few days later they went on to Windsor and held further talks about Wolsey’s papal aspirations. From there they continued on towards Southampton, signing treaties along the way.

The Mary Rose was moored at Southampton and Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey, was aboard. He was busy writing stroppy letters to Wolsey about the lack of victuals and the uncooperative Venetian sailors. Howard had been appointed Admiral of the Fleet. That is to say, he was in charge of both the English and the Spanish navies, which were tasked with returning Charles to Spain unharmed.

At the end of June, Howard sailed west from Southampton towards Dartmouth. He waited at Dartmouth and by 1 July 1522 had sailed across the Channel with his task force and was on the lookout for any maritime threat to Charles’s route home. He sacked the French port of Morlaix. He then sailed west to Saint-Pol-de-Léon and burned it down and then sailed on to the most westerly port in France, Le Conquet, and burned that down too.

Howard and the Mary Rose had made the way safe, and Charles left England from Southampton for Spain on 7 July.

Charles’s Broken Pledge

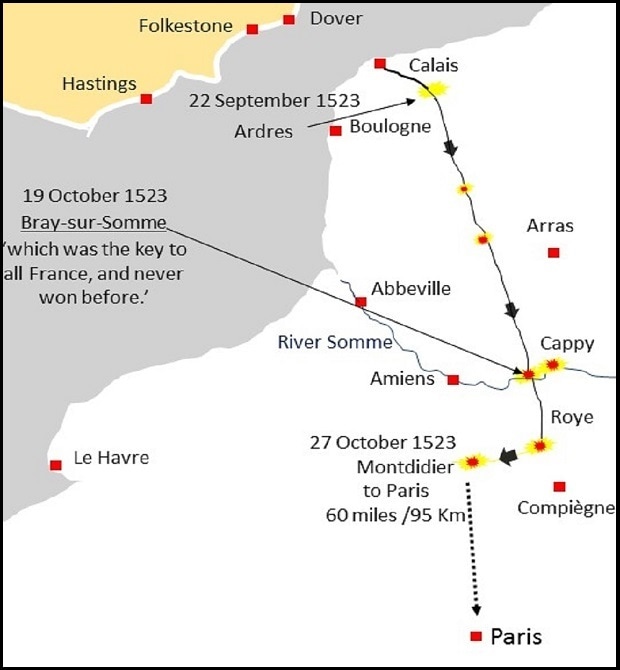

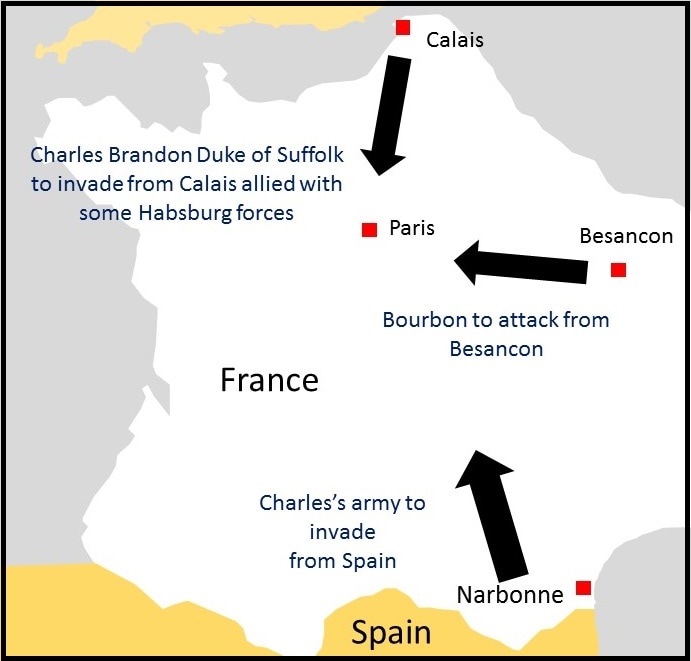

The invasion of France began in early autumn 1523, and the Duke of Suffolk Charles Brandon left Calais with his troops on 19 September.

Within a few days, news arrived that Pope Adrian had died on 14 September. The timing of this for Wolsey couldn’t have been more spectacular if he had designed it himself. Now his time had come, surely?

The cardinal waited for the outcome of this latest papal election. Brandon pushed on into France and made impressive progress south towards Paris. Wolsey had expected to hear quickly from Rome. He expected his election to be a formality and exchanged correspondence with Pace and Hannibal in Rome.

Then he became pensive: on 3 November he was telling Henry that there would never be a better chance of enforcing his entitlement to the French crown. Two weeks earlier, he had told the king that there was no money to pay the troops in November unless Henry could spare £10,000 out of his own pocket.

Time went on, and there were more letters but still no real news. He paced this way and that way; he clicked his heels, twiddled his thumbs and counted sheep through the night.

Then it came: the news. The Medici family had recovered the papacy.

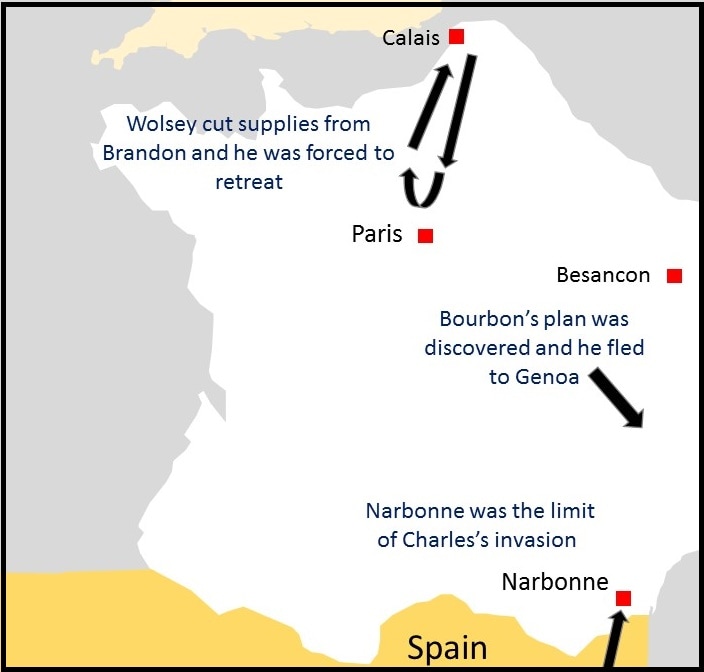

Brandon was waiting for battering rams to knock down the walls of Paris; the city was there for the taking but Wolsey was not the new pope.

Wolsey was devastated. That was it for him and the Habsburgs. They had used him; the scroungers had used the protection of his navy and had used him to secure the Netherlands and he had got nothing out of it all.

Montdidier was the furthest point of Brandon’s advance. While he was there he did not receive pay for his troops, reinforcements or his battering rams for the walls of Paris, and the 1523 campaign collapsed around him.

In early January 1524, Wolsey wrote to William Knight with instruction to pass on his feelings to Margaret, Charles’s regent in the Netherlands.

‘He [Knight] is to remind her of the king’s endeavours to compose the differences between the French king and her nephew, and his final declaration against Francis, which drew on a war with Scotland, and deprived him of the money due to him from France.

Since that time he has carried on the war against the common enemy; by which means the emperor has been able to attend to Spain, has preserved the Low Countries, passed quietly into Spain, recovered Milan, Jeanes, and Tournay, redeemed the pension of Naples, and is freed from his bond to marry the French king’s daughter, to which he was bound by the treaty of Noyon. The King is rejoiced at his success, but still nothing has been done for the King’s profit, and no portion of his inheritance recovered.’

No Place for Catherine in Wolsey’s New Francophile England

By the time Knight had delivered the rebuke, Wolsey had already decided his interests were better served away from the Habsburgs. The de facto ruler of England had decided to ally himself with the Valois dynasty and began talks, secretly from Henry at first, with French agents, and in August the following year signed the Treaty of the More. The formal alliance would probably have been reached more quickly but for the events in Pavia on Francis’s birthday, 24 February 1525.

When Wolsey made that decision to break with the Habsburgs, possibly during the Christmas of 1523, England’s break with Rome began.

Wolsey never forgave Charles. The union between England and the empire and between the Tudors and the Habsburgs had been secured with the marriage of Henry to Catherine of Aragon. So far as Wolsey was concerned, this union, both the marriage and the political alliance, had to go; it was unsustainable and Henry must divorce Catherine.

While he was there hostilities broke out in both northern and southern Europe which had the effect of placing Charles in mortal danger for the return voyage to Spain in 1522.

The Mary Rose, one of the most famous English warships ever built, was instrumental in returning the Spanish king home safely.

However, the exploits of English naval prowess in support of Spain during the summer of 1522 led to the English repudiation of the Habsburgs and the eventual split from Rome.

Charles V, the King of Spain, was elected Holy Roman Emperor in 1519 by a unanimous vote, defeating his principle rival Francis I, the King of France. The effect of his election was to unite the territories Charles had inherited from his maternal grandfather, Ferdinand, with those of his paternal grandfather, Maximilian, in the name of Habsburg. For the rest of their lives, Valois Francis and Habsburg Charles would be bitter enemies.

The ceremony for the coronation of the Holy Roman Emperor, established over many centuries, was a series of rituals, the first of which took place in Aachen, in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. This presented some difficulties for Charles because at the time of his election he lived in Spain.

The English Channel and the Imperial Crown

There was peace in Europe in 1519 because the Treaty of London, organised in 1518 by Thomas Wolsey, Cardinal Archbishop of York and Papal Legate, had been upheld. Any peace, however, between the Habsburg and Valois dynasties was fragile and was likely to be broken at any moment. Francis held military sway in northern Italy but Charles needed to establish communications between his vast territories now united under one sceptre in Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain. There were two alternative routes, either through the Strait of Dover to the port of Flushing (Vlissingen) in the Netherlands or from Barcelona to Genoa and then through Millan to the Tyrol. Innsbruck to Aachen, however, was still another 450 miles overland, and by going that way he would always be vulnerable to attack from France, and in the Mediterranean he would also be threatened by the Turks.

Any French threat in the Strait of Dover, however, could be parried by the alliance with England, which was sealed by his aunt Catherine of Aragon’s marriage to Henry VIII. England possessed a powerful navy, and Uncle Henry would be flattered to be the first monarch to receive the Holy Roman Emperor elect as a guest. The original plan was for Charles to disembark at Southampton and travel overland, meeting up again with his ships at Dover, re-embarking there and so avoiding the Strait of Dover altogether.

Cardinal Wolsey placed himself in charge of the arrangements on the English side.

Wolsey's Seasaw

For the time being, England was pivotal in the balance of power between Valois France on the one side and the expanding Habsburg Empire on the other. The infinitely ambitious Wolsey had by this time appointed himself as a sort of steward of Christendom, the wise man presiding over the three inexperienced young monarchs, Charles, aged nineteen, Francis, twenty-four and Henry, twenty-eight.

Wolsey’s career with Henry VIII had begun with him as the youthful king’s almoner; he was then promoted to be Bishop of Lincoln, and after that very quickly became the Archbishop of York, then Cardinal Archbishop and then the Papal Legate in England. Now he was after the top job, the papacy itself.

Charles set sail from La Carruna and left Adrian of Utrecht, his former tutor and adviser in the Netherlands, with the daunting task of administering the kingdom of Spain as regent during his absence. Adrian had been a senior administrator in Spain since 1515.

Wolsey, as Charles sailed north, was erring towards the French and King Francis for support in relation to his aspirations to become pope. In return, he pledged England’s political and military assistance to France with the intention of tipping the balance of power in favour of the Valois dynasty over the Hapsburgs, but Wolsey was always open to an improved arrangement.

The Field of the Cloth of Gold

The French king and Henry VIII had often expressed a desire to meet each other and so Wolsey arranged an outlandishly lavish event that became known as the Field of the Cloth of Gold, infamous for its glamour, extravagance and apparent lack of political significance.

Francis, at some point during it all, beat Henry at wrestling, which is perhaps worthy of note.

Anyway, the staging of such an event was a logistical marvel in its day and would still be a remarkable achievement today. The total number of Henry’s company for the revels was estimated at 4,000 people and over 2,000 horses and Queen Catherine’s at over 1,000 people and more than 750 horses. There were dukes and earls, bishops, barons and a marquis, together with an army of priests. Then there were tents, timber for buildings, costumes for revels, the king’s bed, all the paraphernalia for the jousting, marvellous statues of ancient princes, probably a kitchen sink or two, and so on and so on. All this was shipped across to France by the splendid power of the English navy.

A Maritime Spectacular

Charles made good time from Spain and, rather than land at Southampton, Wolsey rowed out to meet him, and for his trouble Charles granted him the financial rewards of an entire Spanish bishopric and the substantial part of the revenues of another.

On Whit Sunday, 27 May 1520, Charles rode at the head of a procession from Dover to Canterbury, where the great royal meeting took place and Henry VIII and Queen Catherine embraced their nephew for the first time. Over the next few days, some treaties were signed and then Charles rode back to Dover and sailed on to Flushing while Henry and Wolsey headed to Calais and then on to the jolly in the field.

After the Field of Cloth of Gold, Henry and Wolsey met Charles again at Gravelines, a few miles north of Calais.

All had gone safely for Charles, and he was crowned with the Iron Crown of Lombardy in the great cathedral of Charlemagne in Aachen on 23 July 1520.The emperor was grateful for the part Wolsey had played in his secure arrival and must have thought sailing back to Spain from the Netherlands, if matters were arranged and managed with the same efficiency as the outward journey, would be a breeze.

Back to War

However, soon after Charles was crowned, the peace with France that had held since 1518 was shattered. By the spring of 1521, fighting had broken out in both Luxemburg and Navarre. Each side blamed the other. Accusations flew on one side that the Valois dynasty had started it and on the other side that the Habsburg dynasty had started it; it was even rumoured that some third party had started it. For Charles, who needed to get back to Spain, this was a dangerous situation.

For Wolsey, the arch negotiator, the resulting situation could not have been more convenient if he had engineered it himself. Charles was stuck in the Netherlands when he soon needed to be in Spain but he would be in mortal danger if he left by either land or sea.

Calais, Bruges and Double-Dealing

Wolsey was soon in action: he pulled on his arbiter’s hat, marshalled his great entourage, which included Thomas Ruthall, Cuthbert Tunstall and Thomas More, and set off across the Channel, arriving at Calais on 2 August 1522. The fighting continued unabated, and ostensibly he was there to direct a peace conference. The first session was held on 7 August, and the Habsburg and Valois representatives were present. Charles waited on safe territory in Bruges, from where he wrote to Wolsey and asked the cardinal to go and meet him there.

In response, Wolsey, supposedly the impartial mediator, bluffed the French and went off to meet the emperor in Bruges, where they negotiated a treaty to their own advantage but excluding and to the detriment of the French. The treaty contracted Charles to a future marriage with Henry’s daughter Princess Mary; she was five at the time and of course the marriage never happened.

Beyond all the marriage stipulations, however, most of the remainder of the treaty dealt with Charles’s return to Spain the following spring and the protection he would receive on the journey from the English navy. The return was to be coordinated with a joint, simultaneous declaration of war against France. Wolsey agreed to all this and in return Charles promised to make him pope.

Death of a Pope, Charles on the Hop

It was 29 August before the cardinal arrived back in Calais, and he and his diplomats, one of whom was Thomas Boleyn, had to choreograph some deft diplomatic moves to persuade the French delegation that there had been no double-dealing in Bruges. Indeed the peace talks continued on until November 1521, and Wolsey’s main purpose from that point on was to fool the French into believing England was friendly and neutral.

Wolsey, with his pledge from Charles that he would be the next pope, sailed back to England on 28 November 1521.

Pope Leo X died on 1 December.

He died so suddenly that there was no time to administer the last sacraments. The timing of his death could not have been more spectacular if Wolsey had contrived it himself. Wolsey was entered as a candidate for the subsequent papal election.

The sudden turn of events caught Charles on the hop, however; conveniently for him, when the election was held rival Italian factions caused chaos in Rome. The infighting allowed Charles to slip Adrian, his regent in Spain, into the papal office as Pope Adrian VI. With that appointment, the emperor could stall Wolsey, bluff him with a story as a sop about Adrian being a subordinate stopgap to keep the throne warm until he got back to Spain and could sort things out in Wolsey’s favour. He also told Adrian to appoint Wolsey as Abbott of St Albans, which was one of the richest monasteries in England.

Spain Lauds the English Armáda

Adrian, therefore, was the pope but, for now, a pope who was resident in Spain. Perhaps that was where Charles intended him to stay.

The spring of 1522 arrived and, having reappointed Margaret as regent, Charles departed from Brussels for Spain on 23 May. The Bruges plan to get him there safely was put into operation. Henry VIII’s herald was despatched to France to declare war on the duped French. Charles arrived at Calais on 26 May and crossed to Dover the next day escorted by the English fleet with a complement of over 10,000 men.

Francis was handed the war declaration in Lyon on 29 May. It seems he was not completely surprised – perhaps Wolsey’s bluffing had not been so convincing.

On 6 June, Charles and Henry went from Greenwich to London, surrounded along the way by cheering crowds. Amid all the pomp and ceremony, a few days later they went on to Windsor and held further talks about Wolsey’s papal aspirations. From there they continued on towards Southampton, signing treaties along the way.

The Mary Rose was moored at Southampton and Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey, was aboard. He was busy writing stroppy letters to Wolsey about the lack of victuals and the uncooperative Venetian sailors. Howard had been appointed Admiral of the Fleet. That is to say, he was in charge of both the English and the Spanish navies, which were tasked with returning Charles to Spain unharmed.

At the end of June, Howard sailed west from Southampton towards Dartmouth. He waited at Dartmouth and by 1 July 1522 had sailed across the Channel with his task force and was on the lookout for any maritime threat to Charles’s route home. He sacked the French port of Morlaix. He then sailed west to Saint-Pol-de-Léon and burned it down and then sailed on to the most westerly port in France, Le Conquet, and burned that down too.

Howard and the Mary Rose had made the way safe, and Charles left England from Southampton for Spain on 7 July.

Charles’s Broken Pledge

The invasion of France began in early autumn 1523, and the Duke of Suffolk Charles Brandon left Calais with his troops on 19 September.

Within a few days, news arrived that Pope Adrian had died on 14 September. The timing of this for Wolsey couldn’t have been more spectacular if he had designed it himself. Now his time had come, surely?

The cardinal waited for the outcome of this latest papal election. Brandon pushed on into France and made impressive progress south towards Paris. Wolsey had expected to hear quickly from Rome. He expected his election to be a formality and exchanged correspondence with Pace and Hannibal in Rome.

Then he became pensive: on 3 November he was telling Henry that there would never be a better chance of enforcing his entitlement to the French crown. Two weeks earlier, he had told the king that there was no money to pay the troops in November unless Henry could spare £10,000 out of his own pocket.

Time went on, and there were more letters but still no real news. He paced this way and that way; he clicked his heels, twiddled his thumbs and counted sheep through the night.

Then it came: the news. The Medici family had recovered the papacy.

Brandon was waiting for battering rams to knock down the walls of Paris; the city was there for the taking but Wolsey was not the new pope.

Wolsey was devastated. That was it for him and the Habsburgs. They had used him; the scroungers had used the protection of his navy and had used him to secure the Netherlands and he had got nothing out of it all.

Montdidier was the furthest point of Brandon’s advance. While he was there he did not receive pay for his troops, reinforcements or his battering rams for the walls of Paris, and the 1523 campaign collapsed around him.

In early January 1524, Wolsey wrote to William Knight with instruction to pass on his feelings to Margaret, Charles’s regent in the Netherlands.

‘He [Knight] is to remind her of the king’s endeavours to compose the differences between the French king and her nephew, and his final declaration against Francis, which drew on a war with Scotland, and deprived him of the money due to him from France.

Since that time he has carried on the war against the common enemy; by which means the emperor has been able to attend to Spain, has preserved the Low Countries, passed quietly into Spain, recovered Milan, Jeanes, and Tournay, redeemed the pension of Naples, and is freed from his bond to marry the French king’s daughter, to which he was bound by the treaty of Noyon. The King is rejoiced at his success, but still nothing has been done for the King’s profit, and no portion of his inheritance recovered.’

No Place for Catherine in Wolsey’s New Francophile England

By the time Knight had delivered the rebuke, Wolsey had already decided his interests were better served away from the Habsburgs. The de facto ruler of England had decided to ally himself with the Valois dynasty and began talks, secretly from Henry at first, with French agents, and in August the following year signed the Treaty of the More. The formal alliance would probably have been reached more quickly but for the events in Pavia on Francis’s birthday, 24 February 1525.

When Wolsey made that decision to break with the Habsburgs, possibly during the Christmas of 1523, England’s break with Rome began.

Wolsey never forgave Charles. The union between England and the empire and between the Tudors and the Habsburgs had been secured with the marriage of Henry to Catherine of Aragon. So far as Wolsey was concerned, this union, both the marriage and the political alliance, had to go; it was unsustainable and Henry must divorce Catherine.