Henry VIII, the Reign

Part 53

Henry VIII’s Death, Will and Executors

Henry VIII’s Death, Will and Executors

Edward seymour

Edward seymour

Thomas Howard

Thomas Howard

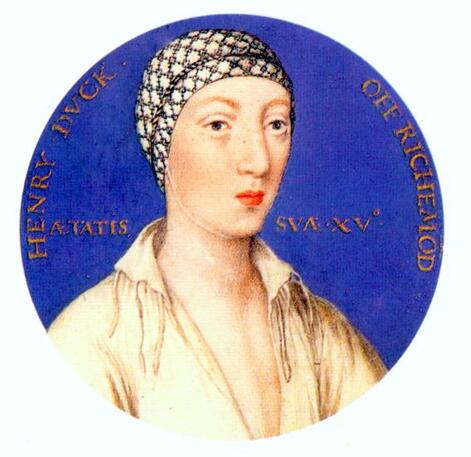

Henry Fiztroy

Henry Fiztroy

|

Henry VIII, the Reign.

|

Henry VIII, the Reign.

|