Henry VIII, the Reign

Part Forty - Three

Privy Council, Culpeper, Progress and Execution

Privy Council, Culpeper, Progress and Execution

Katherine Howard

Katherine Howard

|

John Dudley

John Dudley

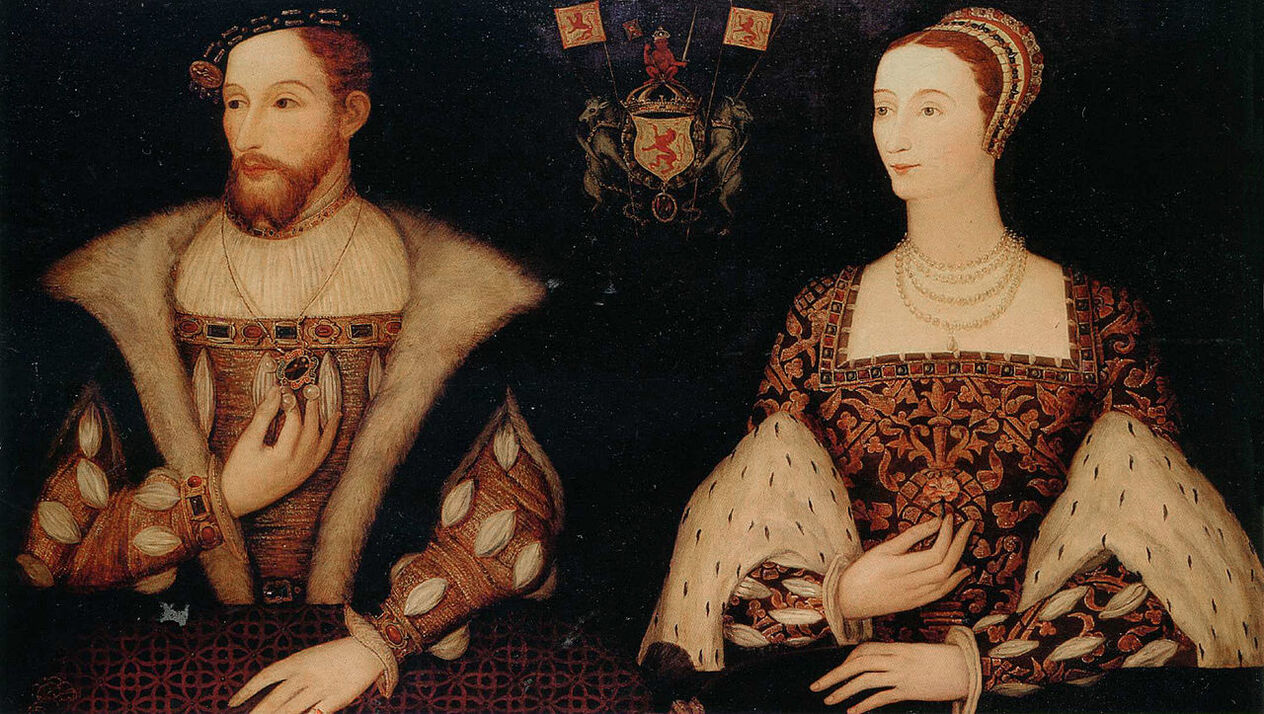

James and Mary

James and Mary

|

Henry VIII, the Reign.

|

Henry VIII, the Reign.

|