Henry VIII, the Reign

The Pilgrimage of Grace

and

The Lincolnshire Rising

The Lincolnshire Rising

also known as

The Rising of the North

|

Pilgrimage of Grace -

|

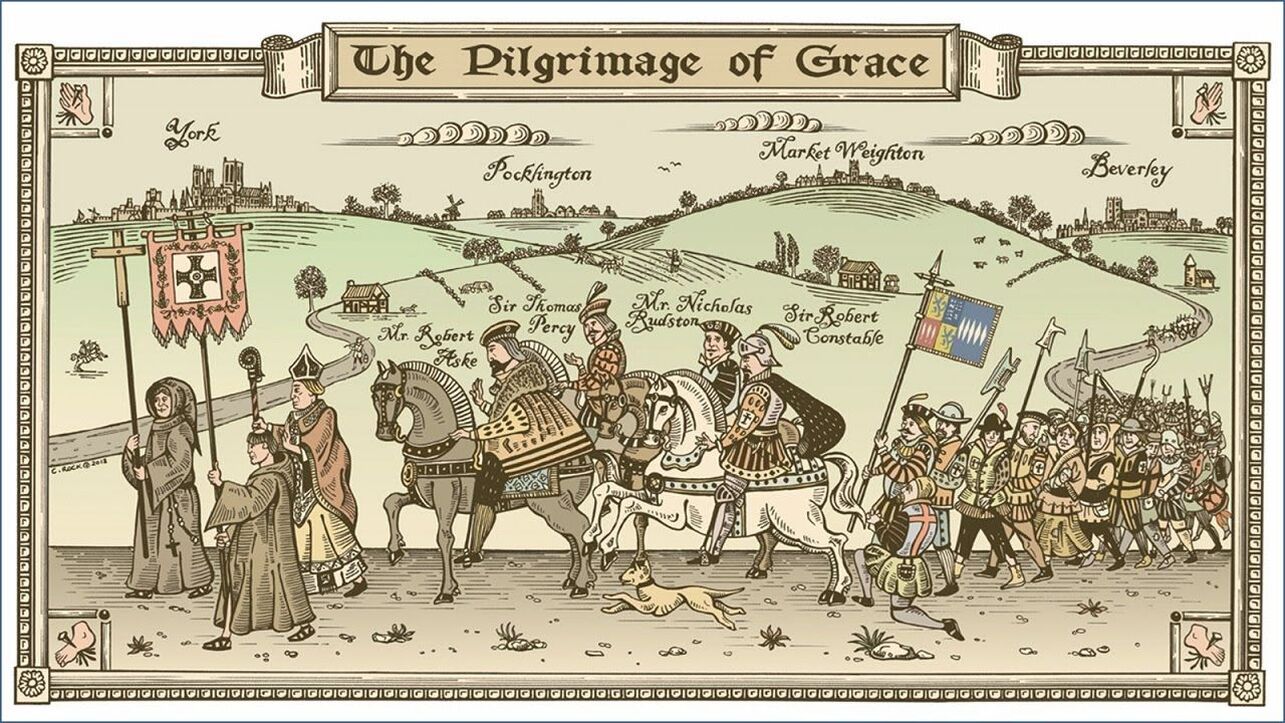

The Pilgrimage of Grace was the name given to the massive uprising and rebellion in the north of

England that began in Lincolnshire. It had the strength of numbers to oust the ruling regime of Henry VIII

England that began in Lincolnshire. It had the strength of numbers to oust the ruling regime of Henry VIII

Men and women returned from the fields, the harvest of 1536 was in.

The sickles, scythes and fagging-hooks were cleaned off after their toil, but this year the tools had a secondary use.

These aggrieved Englishmen intended to use them for another purpose - weapons for a violent and bloody uprising.

A rebellion began in Lincolnshire against Henry VIII and his rulers and then the insurrection spread across northern England.

By 26 October 1536 nearly 40,000 rebels were marching south towards Doncaster to cross the bridge there, and if they marched onward south to take London thousands more were prepared to join them.

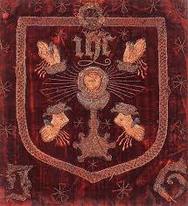

Under the banner of the Five Wounds of Christ together with the flags and pennants of their local insignia the road was open for the pilgrims to oust the ruling regime…

The sickles, scythes and fagging-hooks were cleaned off after their toil, but this year the tools had a secondary use.

These aggrieved Englishmen intended to use them for another purpose - weapons for a violent and bloody uprising.

A rebellion began in Lincolnshire against Henry VIII and his rulers and then the insurrection spread across northern England.

By 26 October 1536 nearly 40,000 rebels were marching south towards Doncaster to cross the bridge there, and if they marched onward south to take London thousands more were prepared to join them.

Under the banner of the Five Wounds of Christ together with the flags and pennants of their local insignia the road was open for the pilgrims to oust the ruling regime…

The Lincolnshire Rising

The Lincolnshire Rising

1536: England at a Crossroads

Henry VIII reigned from 1509 to 1547, almost 38 years, and the most dramatic of those years was 1536.

On 7 January, Catherine of Aragon died, murdered, some claimed; the king was seriously injured falling off his horse while jousting; Anne Boleyn miscarried; the dissolution of the monasteries began; Anne Boleyn was accused of adultery, among other charges, and was executed; Thomas Cromwell became Vicegerent over ecclesiastical affairs; Henry got married again, this time to Jane Seymour; the future Queen Elizabeth was declared a bastard the future Queen Mary was declared a bastard; aged seventeen, the king’s son, Henry Fitzroy, already a bastard, died; the ten articles of doctrine were published; and Henry celebrated his forty-fifth birthday, all before the autumn harvest was in.

For years, Wolsey, Boleyn and Cromwell had harried, browbeaten and cajoled Henry VIII. In 1536, Thomas Cromwell was taking his turn at the helm of government, and in that year great swathes of the religious conservative population had had enough of his interference in the administration of the country. They wanted their sovereign to be allowed some control. By mid-October, after the harvest was in, forty thousand men in arms stood ready at Pontefract Castle to march south and overthrow not Henry VIII but the regime around him that governed.

If they had marched south and had not been placated, England and an acquiescent Henry VIII, together with all of a reunited Christendom, would have reverted to the authority of the pope.

The decision not to march was pivotal in the history of the Christendom.

Henry VIII reigned from 1509 to 1547, almost 38 years, and the most dramatic of those years was 1536.

On 7 January, Catherine of Aragon died, murdered, some claimed; the king was seriously injured falling off his horse while jousting; Anne Boleyn miscarried; the dissolution of the monasteries began; Anne Boleyn was accused of adultery, among other charges, and was executed; Thomas Cromwell became Vicegerent over ecclesiastical affairs; Henry got married again, this time to Jane Seymour; the future Queen Elizabeth was declared a bastard the future Queen Mary was declared a bastard; aged seventeen, the king’s son, Henry Fitzroy, already a bastard, died; the ten articles of doctrine were published; and Henry celebrated his forty-fifth birthday, all before the autumn harvest was in.

For years, Wolsey, Boleyn and Cromwell had harried, browbeaten and cajoled Henry VIII. In 1536, Thomas Cromwell was taking his turn at the helm of government, and in that year great swathes of the religious conservative population had had enough of his interference in the administration of the country. They wanted their sovereign to be allowed some control. By mid-October, after the harvest was in, forty thousand men in arms stood ready at Pontefract Castle to march south and overthrow not Henry VIII but the regime around him that governed.

If they had marched south and had not been placated, England and an acquiescent Henry VIII, together with all of a reunited Christendom, would have reverted to the authority of the pope.

The decision not to march was pivotal in the history of the Christendom.

|

The Architects of Rebellion

Lord Thomas Darcy of Templehurst, Yorkshire, had been Cardinal Thomas Wolsey’s most ardent critic in the 1520s and had drawn up a list of charges against him some five months before his fall and three months before his demise it was Darcy who had suggested that praemunire was the best way of dealing with the cardinal’s offences. From Darcy’s point of view, the change of regime, from Wolsey’s rule to the Boleyn domination, had done nothing to correct the flawed authority of Henry VIII over his kingdom. Now Cromwell and Seymour had their hands on the rudder, Henry was ever the thrall of some interfering faction, Darcy and his adherents yearned for the old ways. They hankered for the decisiveness of this willow backed king’s father and grandmother. In 1534, Darcy and his ‘brother’, as he called him, Lord John Hussey of Sleaford in Lincolnshire, began what became a series of meetings with Eustace Chapuys, Charles V’s ambassador in London. The purpose of the meetings was to persuade Chapuys and to convince the Emperor to launch an invasion of England that would be supported by most English people in a coordinated uprising and so restore Catholic doctrine to Henry VIII’s kingdom. |

People Profiles

|

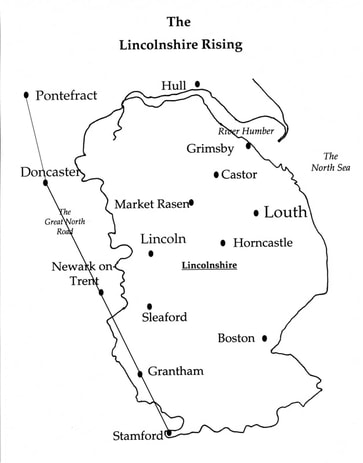

First Lincolnshire was Up

In the autumn of 1536 in Louth, Lincolnshire, an uprising did begin. There were commissioners working in Lincolnshire at that time, and the first of the lesser monasteries were being closed. Precisely what sparked it and why it began in Louth has never been absolutely clear, but it spread at the speed of the sound of church bells as they were rung in back rounds (ascending pitch, tenor to treble) across the county, and all of Lincolnshire rose up.

Within days, thousands had assembled at Lincoln Cathedral, and from there the common people issued five articles of grievance addressed to Henry VIII.

The noblemen organising the rebels, Hussey and Darcy in particular, were familiar with the workings of government in London and of those with the greatest influence who ran the country, and so the allegedly rude and common people of Lincolnshire were sufficiently well informed and could name people individually.

The Bishop of Lincoln’s registrar had arrived in Louth on 2 October 1536 to carry out a visitation. Led by Nicholas Melton, known as Captain Cobbler, the townsfolk seized him, and forced him, or at the very least succeeded in persuading him, to swear an oath of allegiance to their cause.

The registrar was fortunate, because when the rebels caught a hold of the Bishop’s Chancellor, Doctor Raynes, in Horncastle, they bludgeoned him to death. However, as mayhem engulfed the county, Lord Hussey left. Yorkshire was not yet ready to join the rebellion and things were not going entirely to plan; coordination with the Yorkshire rebels was lacking and no help had arrived from the Continent.

A response to the list of grievances arrived from London on 10 October 1536, and it was full of threats and insults. Lacking the support of their allies north of the Humber and expectations of backing from the Low Countries, the Lincolnshire Rising stalled. The men of the Horncastle multitude wound their way home and hung up their banner depicting the five wounds of Christ in the church.

Then Yorkshire was up.

In the autumn of 1536 in Louth, Lincolnshire, an uprising did begin. There were commissioners working in Lincolnshire at that time, and the first of the lesser monasteries were being closed. Precisely what sparked it and why it began in Louth has never been absolutely clear, but it spread at the speed of the sound of church bells as they were rung in back rounds (ascending pitch, tenor to treble) across the county, and all of Lincolnshire rose up.

Within days, thousands had assembled at Lincoln Cathedral, and from there the common people issued five articles of grievance addressed to Henry VIII.

The noblemen organising the rebels, Hussey and Darcy in particular, were familiar with the workings of government in London and of those with the greatest influence who ran the country, and so the allegedly rude and common people of Lincolnshire were sufficiently well informed and could name people individually.

The Bishop of Lincoln’s registrar had arrived in Louth on 2 October 1536 to carry out a visitation. Led by Nicholas Melton, known as Captain Cobbler, the townsfolk seized him, and forced him, or at the very least succeeded in persuading him, to swear an oath of allegiance to their cause.

The registrar was fortunate, because when the rebels caught a hold of the Bishop’s Chancellor, Doctor Raynes, in Horncastle, they bludgeoned him to death. However, as mayhem engulfed the county, Lord Hussey left. Yorkshire was not yet ready to join the rebellion and things were not going entirely to plan; coordination with the Yorkshire rebels was lacking and no help had arrived from the Continent.

A response to the list of grievances arrived from London on 10 October 1536, and it was full of threats and insults. Lacking the support of their allies north of the Humber and expectations of backing from the Low Countries, the Lincolnshire Rising stalled. The men of the Horncastle multitude wound their way home and hung up their banner depicting the five wounds of Christ in the church.

Then Yorkshire was up.

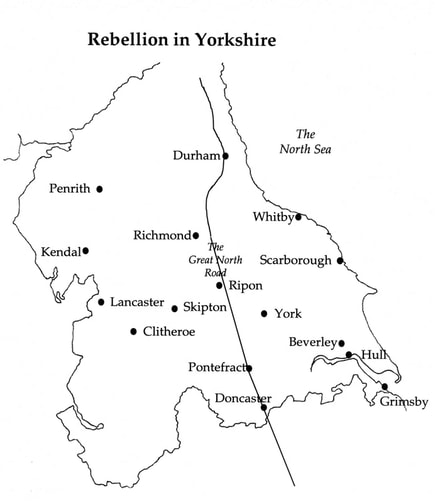

Rebellion in Yorkshire

Rebellion in Yorkshire

Then all the North was Up

While the Lincolnshire rebels, with dampened spirits, were pulling the creases out of the flag, the Yorkshire rising began. On 10 October, north of the Humber, the church bells were ringing in the East and West Ridings and ten thousand men marched on York. Robert Aske, a lawyer, was their leader, and by 16 October the city of York was in the rebels’ hands.

The North Riding was soon up in support, and even before Aske arrived in York, another lawyer, Robert Bowes, was at the head of assemblies in Richmondshire and Richmond itself. Mashamshire rose, as did Sedbergh and Nidderdale, Jervaulx Abbey and Coverham Abbey. Then rebels set out from even further afield, from Durham, Westmoreland and Cumberland, marching under the banners of their beloved saints. Their local leaders took on pseudonyms, Captain Charity, Captain Faith, Captain Pity and Captain Poverty, and they came together as one.

Thomas Darcy controlled the principle stronghold, Pontefract Castle, in the king’s name, and on 19 October he turned the fortress over to the rebels and openly assumed his leadership role alongside Aske.

On the same day, lacking intelligence about Yorkshire, the government force that had been put together to resist the initial Lincolnshire Rising and that made it only as far north as Ampthill in Bedfordshire was disbanded.

The ubiquitous Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, however, was on the move. He was at the head of an army, albeit a fraction of the size of the rebel force at Pontefract, and by 23 October he was at Newark-on-Trent marching north. Despite his own military prowess, he nonetheless proposed negotiation not armed confrontation. He suggested that a small group of pilgrims come a few miles south and meet him when he arrived at Doncaster Bridge. The royal messenger, Thomas Miller, Lancaster Herald, delivered his proposal to the leaders in Pontefract on 24 October. (Miller was executed in the aftermath for complicity with the rebels.)

Norfolk’s proposal caused disagreement in the rebel ranks. They had tens of thousands of well-prepared, armed, disciplined troops who were eager and impatient to move off south and oust Cromwell and his adherents.

While the Lincolnshire rebels, with dampened spirits, were pulling the creases out of the flag, the Yorkshire rising began. On 10 October, north of the Humber, the church bells were ringing in the East and West Ridings and ten thousand men marched on York. Robert Aske, a lawyer, was their leader, and by 16 October the city of York was in the rebels’ hands.

The North Riding was soon up in support, and even before Aske arrived in York, another lawyer, Robert Bowes, was at the head of assemblies in Richmondshire and Richmond itself. Mashamshire rose, as did Sedbergh and Nidderdale, Jervaulx Abbey and Coverham Abbey. Then rebels set out from even further afield, from Durham, Westmoreland and Cumberland, marching under the banners of their beloved saints. Their local leaders took on pseudonyms, Captain Charity, Captain Faith, Captain Pity and Captain Poverty, and they came together as one.

Thomas Darcy controlled the principle stronghold, Pontefract Castle, in the king’s name, and on 19 October he turned the fortress over to the rebels and openly assumed his leadership role alongside Aske.

On the same day, lacking intelligence about Yorkshire, the government force that had been put together to resist the initial Lincolnshire Rising and that made it only as far north as Ampthill in Bedfordshire was disbanded.

The ubiquitous Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, however, was on the move. He was at the head of an army, albeit a fraction of the size of the rebel force at Pontefract, and by 23 October he was at Newark-on-Trent marching north. Despite his own military prowess, he nonetheless proposed negotiation not armed confrontation. He suggested that a small group of pilgrims come a few miles south and meet him when he arrived at Doncaster Bridge. The royal messenger, Thomas Miller, Lancaster Herald, delivered his proposal to the leaders in Pontefract on 24 October. (Miller was executed in the aftermath for complicity with the rebels.)

Norfolk’s proposal caused disagreement in the rebel ranks. They had tens of thousands of well-prepared, armed, disciplined troops who were eager and impatient to move off south and oust Cromwell and his adherents.

Aske to Spend Christmas with Henry VIII

Aske and Darcy, however, believed that by mediating through the Duke of Norfolk they were dealing with the king to the exclusion of Cromwell. Indeed Norfolk was no friend of Cromwell’s.

Darcy had served Henry VII and put his trust in the person, the individual character, who was his son, Henry VIII. He believed that Henry VIII was a man who, left unmolested by the likes of Wolsey, Boleyn and Cromwell, was a good-hearted, generous, God-fearing man.

The two sides talked and, as a consequence, a parliament in York was promised to resolve the grievances, a royal progress to the north of England was pledged and Robert Aske was invited to spend Christmas as Henry VIII’s guest, which he did that December, and a peace agreement was signed on 27 October 1536.

Aske to Spend Christmas with Henry VIII

Aske and Darcy, however, believed that by mediating through the Duke of Norfolk they were dealing with the king to the exclusion of Cromwell. Indeed Norfolk was no friend of Cromwell’s.

Darcy had served Henry VII and put his trust in the person, the individual character, who was his son, Henry VIII. He believed that Henry VIII was a man who, left unmolested by the likes of Wolsey, Boleyn and Cromwell, was a good-hearted, generous, God-fearing man.

The two sides talked and, as a consequence, a parliament in York was promised to resolve the grievances, a royal progress to the north of England was pledged and Robert Aske was invited to spend Christmas as Henry VIII’s guest, which he did that December, and a peace agreement was signed on 27 October 1536.

The Banner of Five Wounds

The Banner of Five Wounds

Misplaced Trust

Darcy and Aske, however, although they might have been dealing via the Duke of Norfolk with the king of their country, were certainly not dealing with the ruler of it. One faction of the rebels had Sir Robert Constable as their spokesman, and they feared the man who did rule, Thomas Cromwell, to such a degree that they demanded to ‘have all the country made sure from the Trent northwards’. In other words, use force to shut him out of the north of England altogether using the River Trent as the barrier. It is little wonder that they were so concerned, because he had threatened that ‘their example shall be fearful to all subjects whiles the world doth endure’. That threat was carried out the following year.

Aske returned north after Christmas, pumped full of royal hospitality; many, however, were unimpressed with what they saw as false promises, including former captains of the autumn rising. Sir Francis Bigod, a descendant of the Bigod Dukes of Norfolk, tried to raise another rebellion and planned to take Hull and Scarborough. This uprising was short-lived, though, and with Cromwell’s threats ringing in his would-be followers’ ears, it petered out, and Bigod was arrested.

Darcy and Aske, however, although they might have been dealing via the Duke of Norfolk with the king of their country, were certainly not dealing with the ruler of it. One faction of the rebels had Sir Robert Constable as their spokesman, and they feared the man who did rule, Thomas Cromwell, to such a degree that they demanded to ‘have all the country made sure from the Trent northwards’. In other words, use force to shut him out of the north of England altogether using the River Trent as the barrier. It is little wonder that they were so concerned, because he had threatened that ‘their example shall be fearful to all subjects whiles the world doth endure’. That threat was carried out the following year.

Aske returned north after Christmas, pumped full of royal hospitality; many, however, were unimpressed with what they saw as false promises, including former captains of the autumn rising. Sir Francis Bigod, a descendant of the Bigod Dukes of Norfolk, tried to raise another rebellion and planned to take Hull and Scarborough. This uprising was short-lived, though, and with Cromwell’s threats ringing in his would-be followers’ ears, it petered out, and Bigod was arrested.

Retribution and the Collapse of Catholic Hopes

The original grievances sent from Lincoln cited that the king’s council was in need of reform. The removal of ministers Cromwell and Rich and like-minded bishops was the root cause of the Pilgrimage of Grace. Everything else stemmed from that, and it branched out in various directions offering support to anything else that could be hung on it.

The pilgrims never had any wish to remove the king and, far from being an indictment of all he stood for, the rebellion was an attempt to institute some consistency it to an administration under his jurisdiction that veered so violently from one tack to the other that he was making enemies all over Christendom. They wanted a decisive, fearless king to stand his ground against self-seeking ministers.

Bishop Stephen Gardiner later wrote, ‘When the tumult was in the north in the time of King Henry VIII, I am sure the King was determined to have given over the supremacy again to the Pope, but the hour was not yet then come, and therefore it went not forward, lest some would have said that he did it for fear.’

The pilgrims never had any wish to remove the king and, far from being an indictment of all he stood for, the rebellion was an attempt to institute some consistency it to an administration under his jurisdiction that veered so violently from one tack to the other that he was making enemies all over Christendom. They wanted a decisive, fearless king to stand his ground against self-seeking ministers.

Bishop Stephen Gardiner later wrote, ‘When the tumult was in the north in the time of King Henry VIII, I am sure the King was determined to have given over the supremacy again to the Pope, but the hour was not yet then come, and therefore it went not forward, lest some would have said that he did it for fear.’

26 October 1536

A truce was agreed and the rebels chose the suicidal policy of entering into an agreement without any security or guarantees. For this failure, they paid the price in the destruction of themselves and their cause. Hundreds, including their leaders, were later executed.

A truce was agreed and the rebels chose the suicidal policy of entering into an agreement without any security or guarantees. For this failure, they paid the price in the destruction of themselves and their cause. Hundreds, including their leaders, were later executed.