Henry VIII, the Reign

Part Twenty - One -

Wolsey’s Visit to Queen Catherine

Wolsey’s Visit to Queen Catherine

Wolsey

Wolsey

Ferdinand

Ferdinand

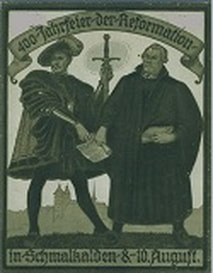

The Schmalkaldic League

The Schmalkaldic League

Catherine's Nephew, Charles V, King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor

Catherine's Nephew, Charles V, King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor

|

Henry VIII, the Reign.

|

Henry VIII, the Reign.

|