Henry VIII, the Reign

Part Twenty - Eight

The Betrothal of Baby Princess Elizabeth Flounders

The Betrothal of Baby Princess Elizabeth Flounders

Thomas Cromwell

Thomas Cromwell

Floundering

Floundering

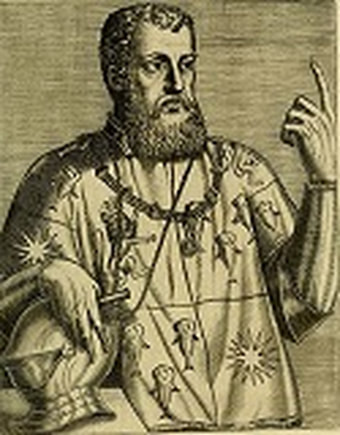

Philippe de Chabot

Philippe de Chabot

Thomas Howard Duke of Norfolk

Thomas Howard Duke of Norfolk

Francis Dauphin of France

Francis Dauphin of France

|

Henry VIII, the Reign.

|

Henry VIII, the Reign.

|